Audrey and I were going through an outdoor market in Seoul’s Jamsil district in early May. I saw a basket of five large, bright-red tomatoes on sale for the low price of 5,000 won. I was raised in a city (Dallas, Texas) and not on a farm, but I like to think I can spot quality produce. I told her, “I have to buy these tomatoes.” When I got them home, however, I was disappointed. The one I cut up and consumed was rather bland. The other four sat in my refrigerator and were tossed after a week. This was not done lightly. I was filled with apprehension since just 74 kilometers from here is the Demilitarized Zone, and north of it live 25.5 million citizens of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. Folks up there—ruling elites excepted—do not discard big, ripe tomatoes just because they fall short of gastronomic perfection.

Although I have lived in South Korea for more than 11 years, I can never figure out people’s attitude toward their brothers and sisters in the north. Some do not care at all, some care a little, and  some care very much. While I would not try to assign percentages to those groups, I place myself among the third. My heart aches when I think of North Koreans’ lack of freedom, the Kim family cult of personality with which they have been inculcated, the gulag and perhaps most of all, hunger. The state-directed command economy that has been in place for more than 70 years does not provide enough food for the people. The fact that just 17 percent of the land is arable and thus suited to agriculture does not explain it. Farming in North Korea is woefully low-tech, with scrawny animals, or even people, pulling plows. Not many fancy John Deere tractors can be seen roaming over the fields there. Although agriculture employs nearly 40 percent of adults, it provides just 22 percent of the country’s gross domestic product.

some care very much. While I would not try to assign percentages to those groups, I place myself among the third. My heart aches when I think of North Koreans’ lack of freedom, the Kim family cult of personality with which they have been inculcated, the gulag and perhaps most of all, hunger. The state-directed command economy that has been in place for more than 70 years does not provide enough food for the people. The fact that just 17 percent of the land is arable and thus suited to agriculture does not explain it. Farming in North Korea is woefully low-tech, with scrawny animals, or even people, pulling plows. Not many fancy John Deere tractors can be seen roaming over the fields there. Although agriculture employs nearly 40 percent of adults, it provides just 22 percent of the country’s gross domestic product.

Massive amounts of food could be imported—the world is painfully aware of the problem—but the Kim regime focuses on development of a nuclear arsenal rather than prosaic matters like putting food into people’s bellies. I am not going to argue for or against the present U.S.-led sanctions, but they could have been avoided had the North Koreans acted more prudently.

“Hunger” and “famine” are two words that are not to be spoken in North Korea. And so the government came up with the chilling euphemism “Arduous March” to denote life there in the mid-1990s. During those years, between 240,000 and 3.5 million people starved to death. Harvests were said to have improved by 1998, but how much? As confirmed by refugees, starvation was back by 2005 and certainly by 2010.

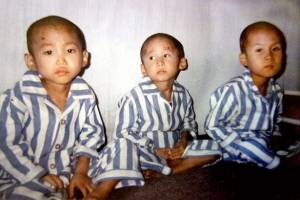

Some observers in South Korea and elsewhere think any notion of famine is an exaggeration and that the wily Kim Jong-un is playing the passive-aggressive game just as his father and grandfather did. Maybe, but I believe the situation north of the border is in fact dire. Again, I refer not to Kim and his generals, whose families eat well, drive nice cars and partake of shopping malls, water parks and golf courses in Pyongyang. My thoughts and concerns are for the average person, the men, women and children who scrounge for just enough to stay alive one day at a time. They live on a monotonous diet of rice, kimchi and corn gruel. When there’s none of that and they are truly desperate, they strip the bark off of trees and eat it, hoping for just a little nutrition. Soup made of grass and leaves is also consumed with regularity. Rats, snakes and vermin are not to be sniffed at. While rare, cannibalism does happen.

The people are not only hungry, they are in poor health. They are smaller than their compatriots to the south, and their lifespan is 11 years shorter. The “Songun” or “military first” principle, in effect now for more than 25 years, prioritizes the army in allocation of resources (food, clean water, clothing, housing, you name it). And yet even soldiers don’t get enough to eat. North Korean soldiers who have escaped to the south in recent years have appeared stunted and emaciated, and  some proved to have parasitic worms in their intestines—clear evidence of malnutrition. Conditions seem to be especially bad in South Hwanghae Province, long considered the bread basket of North Korea. Armed guards these days patrol many of the country’s rice and corn fields. The 2018 harvest was the worst in a decade.

some proved to have parasitic worms in their intestines—clear evidence of malnutrition. Conditions seem to be especially bad in South Hwanghae Province, long considered the bread basket of North Korea. Armed guards these days patrol many of the country’s rice and corn fields. The 2018 harvest was the worst in a decade.

Because the food situation up north ranges from grim to catastrophic, I pondered, fretted and agonized about the tomatoes I had bought in Jamsil. So bland that I regretfully threw them out, they would have been a mouth-watering epicurean delight to North Koreans who eat one meager meal a day—two if they are lucky.

6 Comments

Well written article and it tugs at one’s heartstrings regarding the inhumane treatment of those to the North.

Thanks, Bettye. You are right, and not a day goes by without me thinking of those unfortunate people north of the border.

So much to learn about North Korea. Can propaganda survive for all these years without the truth finally getting out. How brave are those who dare to escape and tell their stories.

Coach, I believe the day will come when this regime falls. We will all be shocked and horrified to learn the details.

Richard-Thanks for writing about this tragic situation. It’s a very tough nut to crack because the N. Koreans were allowed to develop nuclear weapons which provides them tremendous protection from military intervention, and the Chinese are a huge barrier to improving the lot of the North Koreans. Very sad. Kevin

You said it well, Kevin. But I continue to hope for a revolution of some kind up there. It could result from a happy accident. For example, in 2017 the “supreme leader” was only feet from the base of the Hwasong-14 which has untested liquid-fueled rocket engine–highly volatile! He was casually puffing on a cigarette, and none of his generals dared say a word. Can you imagine such an explosion and the results?

Add Comment