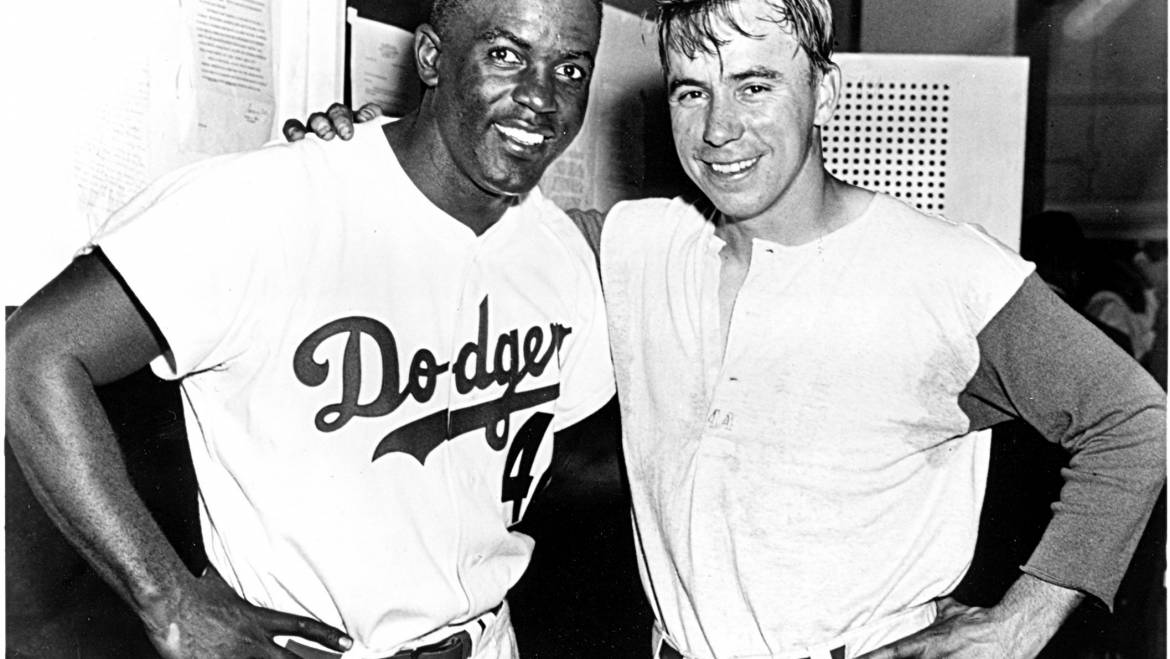

According to Stanley Woodward of the New York Herald Tribune, some major fireworks went off just three weeks after Jackie Robinson began his career with the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947. Certainly there had been opposition to Robinson integrating big league ball. It reached a crescendo, claimed Woodward, when several members of the St. Louis Cardinals plotted to carry out a strike. They would simply refuse to play against the Dodgers in their three-game series from May 6 to 8 at Ebbets Field. Even worse, they might convince players on other National League teams—the New York Giants, Chicago Cubs, Pittsburgh Pirates, Philadelphia  Phillies, Boston Braves and Cincinnati Reds—to join with them. Baseball’s grand experiment would be smashed to bits, and Jim Crow would live on.

Phillies, Boston Braves and Cincinnati Reds—to join with them. Baseball’s grand experiment would be smashed to bits, and Jim Crow would live on.

Poor journalism, to say the least

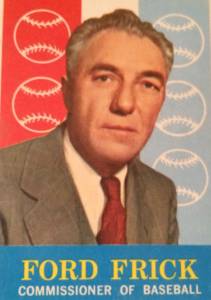

Woodward wrote that Cards owner Sam Breadon contacted National League President Ford Frick and asked him to intervene. The problem was St. Louis’ southerners (although unnamed, they would have included Enos Slaughter of North Carolina, Marty Marion of South Carolina, Eddie Dyer of Louisiana, and Terry Moore and Harry Walker of Alabama). Frick agreed to take care of it. He met with the ringleaders, said he knew of their plan and warned them in no uncertain terms: “If you do this, you will be suspended from the league. You will find that the friends you think you have in the press box will not support you, that you will be outcasts. I do not care if half the league strikes. Those who do will encounter swift retribution and will be suspended, and I don’t care if it wrecks the National League for five years. This is the United States of America, and one citizen has as much right to play as another. The National League will go down the line with Robinson whatever the consequences. You will find if you go through with your intention that you have been guilty of complete madness.”

They retreated, of course. Although Robinson was still subjected to verbal attacks, most notoriously by the Phillies’ Ben Chapman, and rough play for the rest of the season, nothing like a strike occurred. Integration of big league ball was a reality—No. 42 led the Dodgers to the National League pennant, played in 151 of 154 games, batted .297, stole 29 bases and scored 125 runs. The unmistakable hero of the present story, however, was Frick, a native of Indiana who had risen rather quickly from school teacher to PR man to radio broadcaster to ghostwriter for one of Babe Ruth’s books to NL president. (He would later become commissioner of major league baseball.) Frick had held that post for 13 years when Robinson broke the sport’s color barrier. Interestingly, though, he had not been a proponent of integration. He reflected the attitude of most owners, which was to delay and dither and deny. But there he was, Woodward wrote, lambasting those bigoted southern honks and standing up for truth, justice and the American way. Dodgers broadcaster Red Barber praised Frick, saying this was his finest hour. Woodward’s story won the E.P. Dutton Award for best sports reporting of the year and was called the “sports scoop of the century” by Roger Kahn (of The Boys of Summer fame). It was a blockbuster, for sure.

Woodward’s award-winner

I would be the first to agree—if it had happened. But it almost certainly did not. Other writers went in search of more details. Bob Broeg of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, the leader of the critics, wrote that the so-called plot was nothing more than a few disgruntled and boozed-up players yakking among themselves. That Woodward cited no sources and named no names should have been cause for suspicion. He used nebulous phrases in his story like “it is believed…,” “it is understood…” and “we can report….”

Woodward backtracked by saying that no actual meeting had taken place but a letter written; no such letter could be found. He also admitted that he had only talked to Frick, who claimed to have  gotten his information from Breadon and Cardinals trainer Dr. Robert Hyland. So Woodward’s only source for this story was Frick, the man who purportedly faced down a bunch of racist ballplayers. Marion insisted there was never any plan to formulate a strike, as did Dyer, Slaughter and a young superstar named Stan Musial.

gotten his information from Breadon and Cardinals trainer Dr. Robert Hyland. So Woodward’s only source for this story was Frick, the man who purportedly faced down a bunch of racist ballplayers. Marion insisted there was never any plan to formulate a strike, as did Dyer, Slaughter and a young superstar named Stan Musial.

But the story had legs. Jimmy Cannon of the New York Post followed up repeatedly, believing it to be true. Black writers like Sam Lacy and Wendell Smith had no motivation to contest Woodward’s tale and played it up. Kahn, a winner of the E.P. Dutton Award like Woodward, has done the same.

Bogus article for a worthy cause

While Woodward’s story has been largely discredited, it may be said to have served some purpose during that tense 1947 baseball season. If a well of support and compassion for Robinson existed before, it suddenly grew deeper. Quite a few European-Americans who had been sitting on the segregation fence got off; the right and wrong in this case was hard to miss.

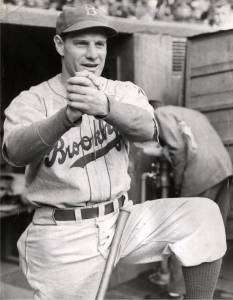

A related story with more substance pertains to Robinson’s own club, the Dodgers. During spring training, outfielder Fred “Dixie” Walker wrote up a petition opposing the plan to integrate. He got a few teammates to sign. Brooklyn president Branch Rickey called in his manager, Leo Durocher, and told him to put the fire out before it spread. Durocher did just that: ‘I’ll tell you what you can do with your petition. If Robinson can win games, I don’t care if he’s white or black or has stripes like a f – – – – – – zebra, he’s going to play for me. I’m the manager of this team, and if I say he plays, he plays. He can take us to the World Series.”

A related story with more substance pertains to Robinson’s own club, the Dodgers. During spring training, outfielder Fred “Dixie” Walker wrote up a petition opposing the plan to integrate. He got a few teammates to sign. Brooklyn president Branch Rickey called in his manager, Leo Durocher, and told him to put the fire out before it spread. Durocher did just that: ‘I’ll tell you what you can do with your petition. If Robinson can win games, I don’t care if he’s white or black or has stripes like a f – – – – – – zebra, he’s going to play for me. I’m the manager of this team, and if I say he plays, he plays. He can take us to the World Series.”

That midnight meeting and that speech, unlike Frick’s facing down the Cards a few weeks later, really did happen.

4 Comments

Richard:

Very nicely done with great detail. The movie ’42’ which came out a few years ago reflected on some of the information you included. It’s incredible to think of so much racism and bigotry at that time.

Rex

Thanks, Rex. I am familiar with that film but never saw it. How did it handle this story? Frick laying into those rebellious players would have been a highly dramatic scene, but I do not think it happened.

Hi Richard-

Very interesting article-I did not know the story about the (possibly) threatened strike. I wish Ford Frick was the NFL commish.

Southerners’ racial attitudes take a hit in the story. I attended college in the 70s and all fifty states were about evenly represented at the school. I found the northerners to be every bit as prejudiced as those from the south.

Kevin, I hope I made clear that the southerners (for all their faults) were being unfairly accused. That’s what made it such an appealing story for Woodward to concoct.

Add Comment