I am a sucker for a good historical episode, and this is one. Please allow me to summarize. On April 15, 1885, three British warships (HMS Agamemnon, HMS Pegasus and HMS Firebrand) and two transport  ships steamed out of Nagasaki and headed west. They came to a three-island archipelago approximately halfway between the Korean mainland and Jejudo. Meeting no resistance from the natives, the Brits took possession—not de jure but de facto. For the next 22 months, they would be in command. John Bull called it “Port Hamilton” in honor of W.A.B. Hamilton, former secretary of the Admiralty. The British Empire in the 19th century grew by 26 million square kilometers and 400 million people. Why not add a little island off Korea’s south coast? From a modern perspective, however, it was a hostile and audacious act.

ships steamed out of Nagasaki and headed west. They came to a three-island archipelago approximately halfway between the Korean mainland and Jejudo. Meeting no resistance from the natives, the Brits took possession—not de jure but de facto. For the next 22 months, they would be in command. John Bull called it “Port Hamilton” in honor of W.A.B. Hamilton, former secretary of the Admiralty. The British Empire in the 19th century grew by 26 million square kilometers and 400 million people. Why not add a little island off Korea’s south coast? From a modern perspective, however, it was a hostile and audacious act.

The quotidian lives of Korean islanders

The locals, whose ancestors had arrived sometime during the Bronze Age, had little contact with the government in Seoul. Taxes were paid intermittently, in the form of rice and salt. There was no military presence and no formal schooling, although literacy was surprisingly high. It was nothing but the people, the land and the surrounding waters. In fact, Seonhodo, Sodo and the much smaller Godo (uninhabited, although I don’t know why) which sat between them, made an excellent harbor, one from which an imperial navy might control trade and movement of ships in the South Sea. For just this reason, the United Kingdom and Russia had been casting covetous eyes on Geomundo for the previous 40 years. The British apparently seized it to preclude the Russians from doing the same. King Gojong, his foreign minister, Kim Yun-sik, and Admiral  Jeong Yeo-chang were outraged when they learned that the Union Jack was flying over a portion of Korean territory, no matter how small or remote. They protested time and again. The paternalistic Brits had the nerve to say they were doing it for the Koreans’ sake, to protect them from the Russkies.

Jeong Yeo-chang were outraged when they learned that the Union Jack was flying over a portion of Korean territory, no matter how small or remote. They protested time and again. The paternalistic Brits had the nerve to say they were doing it for the Koreans’ sake, to protect them from the Russkies.

While the term “unequal treaty” did not come into use until the early 1920s, it surely applies to the United Kingdom–Korea Treaty of 1883. It followed the template created by the Japanese (1876), Americans (1882), Chinese (1882) and Germans (1883), and it was more of the same from the French (1886), Austrians (1892), Belgians (1901) and Danes (1902). When those British sailors dropped anchor in Geomundo Bay, they came in the guise of friends and partners.

Short term…or maybe forever

The Englishmen, practiced in the arts of diplomacy (where saying one thing and meaning another was the norm—unless, of course, it suited their purposes to do otherwise), held all the cards with the Koreans. Diplomats William George Aston, William Richard Carles and Francis Richard Plunkett insisted that the seamen representing Her Majesty were there temporarily, and eventually it proved to be just that. But some of their actions, at least, gave the impression of taking permanent control. They had, after all, unilaterally imposed the Port Hamilton name. Among their bolder proposals was to offer a large loan to Korea, and when it fell behind on making payments, as it surely would, a plausible reason would be at hand for the UK to call Geomundo its own. Had that happened, the Koreans would have been deported.

Relations between the British navy and the islanders were not all bad; the economy got a boost and several hundred men found employment doing unskilled labor. A policy of non-fraternization was strictly enforced, which means the women were treated with respect. No mixed-race babies were left behind. Make no mistake, however—the British were in control. On three occasions, thieves were flogged.

The Russian threat subsided, and the British came to realize that they had overrated Geomundo’s strategic importance in terms of maritime power and trade. They departed with little fanfare on February 27, 1887, and Geomundo fell back into obscurity.

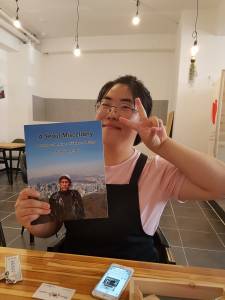

A barista in Yeosu

Determined to see this for myself, I rode the KTX down to Yeosu and found a hotel close to the ferry terminal. I got lucky when I walked into the CKOI coffee shop. The proprietor, Choi Yun-joo, was a native of Geomundo and told me a few helpful things. Most of all, she put me in touch with her aunt, Won Ha-jeong. She ran a coffee shop/minbak there called Veracoat and would be waiting for me at the dock the next day. In return for Yun-joo’s kindness, I signed a copy of A Seoul Miscellany and donated it to her little library. I had been to Yeosu before, in February 2011, mostly to learn about the city’s favorite son—Yi Sun Shin. I walked several kilometers that afternoon and evening, as I would the next two days. I am not asking for sympathy when I state that it was hot and muggy down on the coast.

Determined to see this for myself, I rode the KTX down to Yeosu and found a hotel close to the ferry terminal. I got lucky when I walked into the CKOI coffee shop. The proprietor, Choi Yun-joo, was a native of Geomundo and told me a few helpful things. Most of all, she put me in touch with her aunt, Won Ha-jeong. She ran a coffee shop/minbak there called Veracoat and would be waiting for me at the dock the next day. In return for Yun-joo’s kindness, I signed a copy of A Seoul Miscellany and donated it to her little library. I had been to Yeosu before, in February 2011, mostly to learn about the city’s favorite son—Yi Sun Shin. I walked several kilometers that afternoon and evening, as I would the next two days. I am not asking for sympathy when I state that it was hot and muggy down on the coast.

Directly across from Yeosu Station sat acre after acre of mostly empty buildings, left over from the 2012 Yeosu Expo. It was, by all accounts, successful, with 105 countries participating and more than 8 million visitors. But what to do with all those big purpose-built edifices?

I set the alarm for 5 a.m. on Saturday and was at the ferry terminal at 6:40 to make sure I would get a ticket. I did not, and the next ship was not scheduled to leave for several more hours. Fortunately, the man who ran my hotel was willing to let me back in without charge. I turned on the air-conditioner and read 50 or so pages of The Best American Sports Writing of the [20th] Century, edited by David Halberstam. With some telephonic pleading on my behalf by Audrey in Seoul, I was able to board a large  white-and-blue ship called Joguk. The ferry ride would last 2 ½ hours since we stopped to drop off and pick up passengers at Baekyado, Gaedo, Sonjukdo and Chodo before pulling into the port of Geomundo. The water, mercifully, had been calm, as I feared a repeat of the seasickness I had coming back from Baengnyeongdo in 2014.

white-and-blue ship called Joguk. The ferry ride would last 2 ½ hours since we stopped to drop off and pick up passengers at Baekyado, Gaedo, Sonjukdo and Chodo before pulling into the port of Geomundo. The water, mercifully, had been calm, as I feared a repeat of the seasickness I had coming back from Baengnyeongdo in 2014.

Foreigners are quite uncommon there, so Ha-jeong had no trouble identifying me; my orange University of Texas basketball jersey was a dead giveaway. The room I rented for 24 hours sufficed, even if it had no bed. Ha-jeong was as monolingual as me, but she grasped that I was interested in seeing the cemetery where some of those English mariners are still buried. A sign just down the street showed the way. If only it were that simple! At first, I was walking on a paved road. That petered out, so I kept going on well-worn and then barely worn paths. Sometimes it seemed I was lost. I stopped to examine a sturdy Western-style building topped by a Korean gabled roof and yearned to know its history, but there was nothing to satisfy inquisitive tourists like me. On I went. Then I happened to meet a solitary female mountain climber. She, too, was looking for the aforesaid cemetery. In 15 minutes, we found it.

Buried far from home

Ten men died on the islands during that time, 8,800 kilometers from their homes. Two were killed by a bomb explosion, one drowned, and the others presumably died of natural causes. Here are four names: Charles Dale, William J. Murray, Thomas Oliver and Alex Wood. It’s hard to be mad at these long-deceased guys. Queen Victoria, the prime minister and the men in the House of Lords called the shots. They—not Dale, Murray, Oliver, Wood et al.—decided to come and grab Geomundo.

Ten men died on the islands during that time, 8,800 kilometers from their homes. Two were killed by a bomb explosion, one drowned, and the others presumably died of natural causes. Here are four names: Charles Dale, William J. Murray, Thomas Oliver and Alex Wood. It’s hard to be mad at these long-deceased guys. Queen Victoria, the prime minister and the men in the House of Lords called the shots. They—not Dale, Murray, Oliver, Wood et al.—decided to come and grab Geomundo.

As I sat there pondering historical matters, this woman whose name I never knew waved and was gone. It was all rather comical. In what was left of the day, I walked and found a pair of lighthouses, saw the elementary and middle schools Yun-joo had attended (one of which featured a statue of a young girl savoring a book), and tried unsuccessfully to locate Bultanbong. That, if I understand correctly, is the peak of a mountain from which you can see Jejudo to the southwest. During the Japanese colonial era, it served as an oceanographic observatory.

In both Yeosu and Geomundo, I dined on galchi. This largehead tailfish can be fried or grilled, and its flesh is firm but tender. Galchi is also easy to de-bone. Did you know that it is the tenth-most caught fish  in the world? More than 1.2 million metric tons of galchi are consumed every year.

in the world? More than 1.2 million metric tons of galchi are consumed every year.

Of mermaids, friendly cops and ASU Sun Devils

On Sunday morning, my plan was uncertain. I kind of wanted to see the Noksan lighthouse, located high on a bluff. But I had already been to two lighthouses, and getting there would not be easy. Had I gone, I would have learned more about the legend of the mermaid Shinjike, who had long, dark hair and milky white skin. She saves fishermen in times of peril, or so it is claimed.

I settled instead for a visit to the beach, located on the other side of a long, single-lane bridge at the island of Sodo. I spoke with some people at a restaurant close to the ferry terminal about calling a taxi, but that was obviated when a police car pulled up. Two men in uniform got out and said they would take me there. This has happened before, and it’s a perfect example of how a foreigner is sometimes given special treatment in Korea. They dropped me off at a beach whose length was no more than 100 meters. Two little girls wearing life jackets and swim caps were playing in the water while a dozen adults watched  under an awning. After 20 minutes, I was ready to go back. It would be a long walk, but not too long. And anyway, the scenery was quite pleasing to the eye. I might add that the air was pleasing to the nose—a stark contrast to what obtains in central Seoul. Returning to the city, such as it was, I encountered a nice couple who said they were going to the Noksan lighthouse. I was welcome to join them. “How long would it take?” I asked. “Three hours each way,” they replied. I demurred.

under an awning. After 20 minutes, I was ready to go back. It would be a long walk, but not too long. And anyway, the scenery was quite pleasing to the eye. I might add that the air was pleasing to the nose—a stark contrast to what obtains in central Seoul. Returning to the city, such as it was, I encountered a nice couple who said they were going to the Noksan lighthouse. I was welcome to join them. “How long would it take?” I asked. “Three hours each way,” they replied. I demurred.

Shortly after noon, it was time for me to mosey on over to the ferry terminal. I could not take a chance on missing it since the weather was supposed to get much worse the next day, in which case no ferries would go or come. I did get a ticket. While waiting, I met Dr. Seo Kihwan. He had been scuba diving at Geomundo with friends over the weekend. I learned that he got his Ph.D. in geography at Arizona State and is now working on the massive government complex in Sejong City. This was an express ferry, and it seemed that we arrived shortly after we left. I stopped in at Yun-joo’s coffee shop, telling her thanks and goodbye. On the north-bound KTX coming home, I had the pleasant surprise of meeting Kang Min-goo, one of my helpers on the Committee to Bring Jikji Back to Korea. He introduced me to his fiancée and informed me that he now works as a National Assembly member’s assistant on Yeouido. I was happy to tell Min-goo that our five-year campaign is not over and that I am writing a book about it.

12 Comments

Another enlightening history, Richard. Your obvious passion for all things history floats to the top. You do adore that UT Jersey. I do too.

Ah, Ms Brooks! Thank you for reading and commenting. I would like the UT jersey more if it were bright orange, hahaha.

Richard, you get all the cushy jobs. Just think of how many of us would yearn to be along as you interrogate unsuspecting natives about their homeland? Another most interesting episode in your never-ending joy of discovery.

Thanks, Coach. I try not to take it for granted!

Thanks for another interesting commentary, Richard. Unfortunately, those European colonists, like our American ancestors, believed that they were entitled to seize possessions from they considered to be under developed countries to bolster their economies.

Yes, and this was really not so long ago–1885. They just showed up and said, “We are in charge.”

Another fascinating account! Thanks so much for sharing, Richard.

Well, thank you for reading it, Justin. Note my orange-and-white apparel.

Thanks, Richard, I always learn something interesting from your writing. As you know, I am interested in all things naval so found your account of Britain’s gunboat diplomacy of particular interest. The Brits kept a pretty large contingent of ships on their “China Station” so I guess there were plenty these sorts of incidents. I never heard of galchi-must be a tasty fish to be so popular. Cheers, Kevin

Kevin, you are right–it must have happened a lot. I wonder if there is a parallel between this and the so-called Falkland Islands off the coast of Argentina. I am wondering what my British friend Pippa will think of this story.

Thank you for writing such an interesting piece! I always admire your enthusiasm for learning.

I sometimes wonder how many Koreans know (or choose to know) about this. I guess it’s an unpleasant reminder of how weak they were in the late 19th century. Thanks for reading and commenting, Anthony.

Add Comment