It has been suggested that I am too harsh in calling the Jim Crow college football coaches—Bear Bryant (primarily Alabama), Charley McClendon (LSU), Bobby Dodd (Georgia Tech), Frank Howard (Clemson), Shug Jordan (Auburn), Johnny Vaught (Mississippi), Jess Neely (primarily Rice), Darrell Royal (primarily Texas) and Frank Broyles (primarily Arkansas)—“cowards.” Although I value such honest feedback, I still believe I have characterized these gentlemen accurately.

Bama’s powerful coach actually a weakling

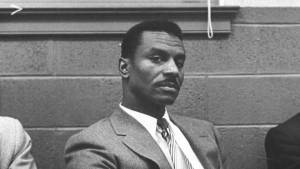

The one who seems to inspire the strongest defense is Bryant, who coached the Crimson Tide from 1958 to 1982. In the first 13 of those seasons, all of his players were European-American; in the last 12, the Bear’s squads were at first nominally and then fully integrated. I see no point in trying to justify his  waiting until 1971 to suit up an African-American player. “But they wouldn’t let him do it any earlier,” I am told, to which I reply, “Who were ‘they’ and were ‘they’ really that much stronger than UA’s legendary football coach?” I posit that Bryant should have gotten on Interstate 20 and driven 58 miles from Tuscaloosa to Birmingham. There he would have found Fred Shuttlesworth, a man who epitomized courage, determination and refusal to give up. Come to think of it, those were the very qualities Bryant sought to inculcate in his players.

waiting until 1971 to suit up an African-American player. “But they wouldn’t let him do it any earlier,” I am told, to which I reply, “Who were ‘they’ and were ‘they’ really that much stronger than UA’s legendary football coach?” I posit that Bryant should have gotten on Interstate 20 and driven 58 miles from Tuscaloosa to Birmingham. There he would have found Fred Shuttlesworth, a man who epitomized courage, determination and refusal to give up. Come to think of it, those were the very qualities Bryant sought to inculcate in his players.

Shuttlesworth (1922−2011) made countless contributions to the civil rights movement. The son of a coal miner/farmer/bootlegger, he was always working to fight racism and improve the quality of life of his fellow African-Americans. He attended a couple of unaccredited colleges and became pastor of Bethel Baptist Church in Birmingham. On Christmas night, 1956, a dozen sticks of dynamite exploded underneath his house. Although it was heavily damaged, Shuttlesworth and his family were unhurt. A policeman sent to investigate said to him, “If I were you, I’d get out of this town as quickly as I could.” He responded thus: “Officer, you’re not me. You go back and tell your Klan brethren that I’m here for the duration.”

Fred Shuttlesworth did not run away from nettlesome problems, he ran toward them. Yes, he sought them out.

He and his wife took their daughters to the segregated Phillips High School and tried to register them for the 1957−1958 school year. A tsunami of cursing and violence fell upon them as a gang of Ku Kluxers  whaled away with brass knuckles, baseball bats and bicycle chains. The police were nowhere to be seen. A heavily bleeding Shuttlesworth managed to drive his family to a hospital for treatment. While there, they gathered and said a prayer of forgiveness.

whaled away with brass knuckles, baseball bats and bicycle chains. The police were nowhere to be seen. A heavily bleeding Shuttlesworth managed to drive his family to a hospital for treatment. While there, they gathered and said a prayer of forgiveness.

KKK feared him

In 1961, the year a CBS documentary called him “the man most feared by Southern racists,” he helped the Freedom Riders when they arrived in Birmingham. The scene at the bus station was pure mayhem as Klansmen beat African- and European-Americans who dared test a recent Supreme Court ruling that guaranteed freedom of interstate travel. Shuttlesworth dived in and mitigated the damage, taking those valiant young people into his own home and nursing their wounds. He then arranged their departure for New Orleans.

Then, of course, came 1963’s Project C, so named by Martin Luther King after discussions with Shuttlesworth. The “C” stood for “confrontation” because the two civil rights giants were determined to confront the implacable segregation and racism that had so long ruled supreme in Birmingham. Verbally and physically, Shuttlesworth battled Bull Connor, the city’s notorious Commissioner of Public Safety.  Connor was his nemesis, his bete noire. During this time a bomb went off in a church, killing four young African-American girls, and marchers were arrested en masse, many having been attacked by baton-wielding cops, fire hoses and snarling German shepherds. One of my favorite Shuttlesworth anecdotes involves the time a Birmingham church (doubling as a civil rights sanctuary) full of people was being besieged by a couple of hundred rabid racists. They were threatening to shoot the place up or burn it down. MLK was on the phone to Attorney General Robert Kennedy, and things looked ominous. Shuttlesworth, not a big man at 5′ 9″ and 152 pounds, fought his way into the church. “Out of the way, out of the way, I’m coming in!” he yelled. The startled mob allowed him to pass.

Connor was his nemesis, his bete noire. During this time a bomb went off in a church, killing four young African-American girls, and marchers were arrested en masse, many having been attacked by baton-wielding cops, fire hoses and snarling German shepherds. One of my favorite Shuttlesworth anecdotes involves the time a Birmingham church (doubling as a civil rights sanctuary) full of people was being besieged by a couple of hundred rabid racists. They were threatening to shoot the place up or burn it down. MLK was on the phone to Attorney General Robert Kennedy, and things looked ominous. Shuttlesworth, not a big man at 5′ 9″ and 152 pounds, fought his way into the church. “Out of the way, out of the way, I’m coming in!” he yelled. The startled mob allowed him to pass.

On March 7, 1965, Shuttlesworth was at the Edmund Pettus Bridge with 550 others. Most, although certainly not all, were African-American. They intended to march on Highway 80 from Selma to Montgomery. But Alabama state troopers, many of them on horseback, were a bit overenthusiastic about halting them. Nightsticks and tear gas were used freely in a brutal attack that was televised all over the USA.

Where was the Bear?

(I wonder what Bear Bryant was doing on March 7, 1965. What if—WHAT IF—he had come to Selma to show his support for the marchers? The dynamic would have been drastically altered. Governor George Wallace, County Sheriff Jim Clark, Mayor Joe Smitherman and all those men doing their bidding that day would have known and been forced into a different stance. Support from the Bama football coach, after his team had come within a whisker of winning the 1964 national championship, would have been electrifying. And what a perfect time for him to say he was going to start recruiting African-American athletes immediately. Needless to say, Bryant would have a wholly different legacy today.)

How many times was Shuttlesworth arrested? He lost count but estimated it was between 30 and 40. He was the plaintiff or defendant in numerous cases, some quite important. He never hesitated to put himself on the line. I am not about to detract from the immense contributions of King, a gutsy man himself. But nobody was more active than Shuttlesworth in pulling down the edifice of segregation and racism. These days, he is honored in Birmingham in many ways, including a street, a park, a statue and the city’s airport. His name is mentioned repeatedly on the Civil Rights Heritage Trail.

He had no fear, which brings me back to Bryant and his fellow Jim Crow football coaches. What, or who, were they so afraid of? Shuttlesworth went nose-to-nose with the Klan and Bull Connor, and he survived. A right-wing booster, a moss-backed administrator, an arch-conservative faculty member, some bigoted players—Bryant, et al. were afraid of these people? I thought they wanted to win football games. As I have said so often it makes my head hurt, maintaining the racial status quo trumped everything else. Their lack of vision (and wisdom and compassion) is all too obvious. The facts point to this conclusion: They were cowardly.

Excuses, excuses

I wish just one of them would have stood up and done his own Project C, confronting the people at his school, talking frankly to the media and if necessary, abandoning the region for the North or West. You think these coaches, all well established in their careers, could not have found employment outside of the South? A simple definition of the word “coward” is “a person who lacks the courage to do or endure dangerous or unpleasant things.” I have never contended that integrating a big-time Southern college football program during those years was easy, but in every case it had to be done. Bryant, McClendon, Dodd, Howard, Jordan, Vaught, Neely, Royal and Broyles—they all deserve to be called cowards. Excuses for these guys? I do not want to hear it!

I wish just one of them would have stood up and done his own Project C, confronting the people at his school, talking frankly to the media and if necessary, abandoning the region for the North or West. You think these coaches, all well established in their careers, could not have found employment outside of the South? A simple definition of the word “coward” is “a person who lacks the courage to do or endure dangerous or unpleasant things.” I have never contended that integrating a big-time Southern college football program during those years was easy, but in every case it had to be done. Bryant, McClendon, Dodd, Howard, Jordan, Vaught, Neely, Royal and Broyles—they all deserve to be called cowards. Excuses for these guys? I do not want to hear it!

Not even his enemies said Fred Shuttlesworth was a coward. They recognized him as a steely, driven and focused man, a worthy foe. He simply would not be intimidated. My admiration for him is boundless.

Add Comment