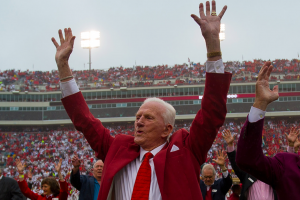

Frank Broyles, the last of the Jim Crow college football coaches, has died. The cause was complications from Alzheimer’s disease; he was 92.

I can find a lot of reasons to admire and respect this man. He was a multi-sport athlete at Georgia Tech in the mid-1940s, and paid his dues as an assistant at Baylor, Florida and his alma mater before getting  the head coaching gig at Missouri. He was in Columbia just one year, 1957, and his record was a mediocre 5-4-1, but Arkansas came calling. He went and stayed the rest of his life as a coach, athletic director and fund raiser. (Broyles’ experience is remarkably similar to that of Darrell Royal. He had several assistant jobs before becoming head coach at Washington in 1956. Although the Huskies went just 5-5, Texas was interested. There was another parallel between Broyles and Royal, as we will see.) In 19 years with the Razorbacks, Broyles’ teams won seven Southwest Conference titles and the 1964 national crown.

the head coaching gig at Missouri. He was in Columbia just one year, 1957, and his record was a mediocre 5-4-1, but Arkansas came calling. He went and stayed the rest of his life as a coach, athletic director and fund raiser. (Broyles’ experience is remarkably similar to that of Darrell Royal. He had several assistant jobs before becoming head coach at Washington in 1956. Although the Huskies went just 5-5, Texas was interested. There was another parallel between Broyles and Royal, as we will see.) In 19 years with the Razorbacks, Broyles’ teams won seven Southwest Conference titles and the 1964 national crown.

Frank’s Hogs could play

I was at the Cotton Bowl on November 13, 1965 to see a game between SMU and Arkansas. The Hogs won, as might be expected, by a score of 24-3. I was impressed. These guys were fast and intense, and they really came to play. They were also entirely European-American, as was Hayden Fry’s varsity team. Fry had been one of Broyles’ assistants in 1962 when he interviewed at SMU. He told President Willis Tate and AD Matty Bell that he would take the job (and its $13,000 salary) on one condition—that he be allowed to field an integrated team. This was a very risky thing to do. Tate and Bell were initially taken aback by Fry’s demand, but they agreed as long he was careful in making his choice. Fry soon made his choice, a speedy receiver / kick returner from Beaumont named Jerry LeVias. Then on the SMU freshman team, LeVias would have a devastating impact on Southwest Conference football in the 1966, 1967 and 1968 seasons.

It’s hard not to speculate about Broyles’ response when he heard what Fry had said in Dallas: “Hayden, you did WHAT?” In no way, shape or form do I wish to accuse Broyles of racism. Being European- American and coming from Decatur, Georgia does not equate to racism. More likely, he was a coward—just like Royal (Hollis, Oklahoma). Both of these men, giants of college football, were cowards when it came to the tough issue of racial integration. They knew it was going to happen. The Civil Rights movement was in full sway, and pressure was building. But they chose to wait just as long as possible to bring in a black player or two. Fry (Eastland and Odessa, Texas) seemed to have a different view. He wanted two things, to win and to do what was right.

American and coming from Decatur, Georgia does not equate to racism. More likely, he was a coward—just like Royal (Hollis, Oklahoma). Both of these men, giants of college football, were cowards when it came to the tough issue of racial integration. They knew it was going to happen. The Civil Rights movement was in full sway, and pressure was building. But they chose to wait just as long as possible to bring in a black player or two. Fry (Eastland and Odessa, Texas) seemed to have a different view. He wanted two things, to win and to do what was right.

No comment

In the mid-1980s, when I was writing Breaking the Ice / Racial Integration of Southwest Conference Football, Royal and Fry gave me multiple interviews. John Bridgers of Baylor, Fred Taylor of TCU, J.T. King of Texas Tech and Bill Yeoman of Houston also made themselves available. Only Broyles declined.

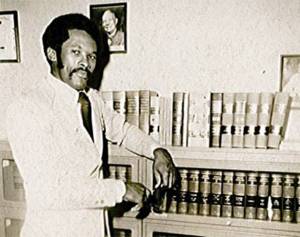

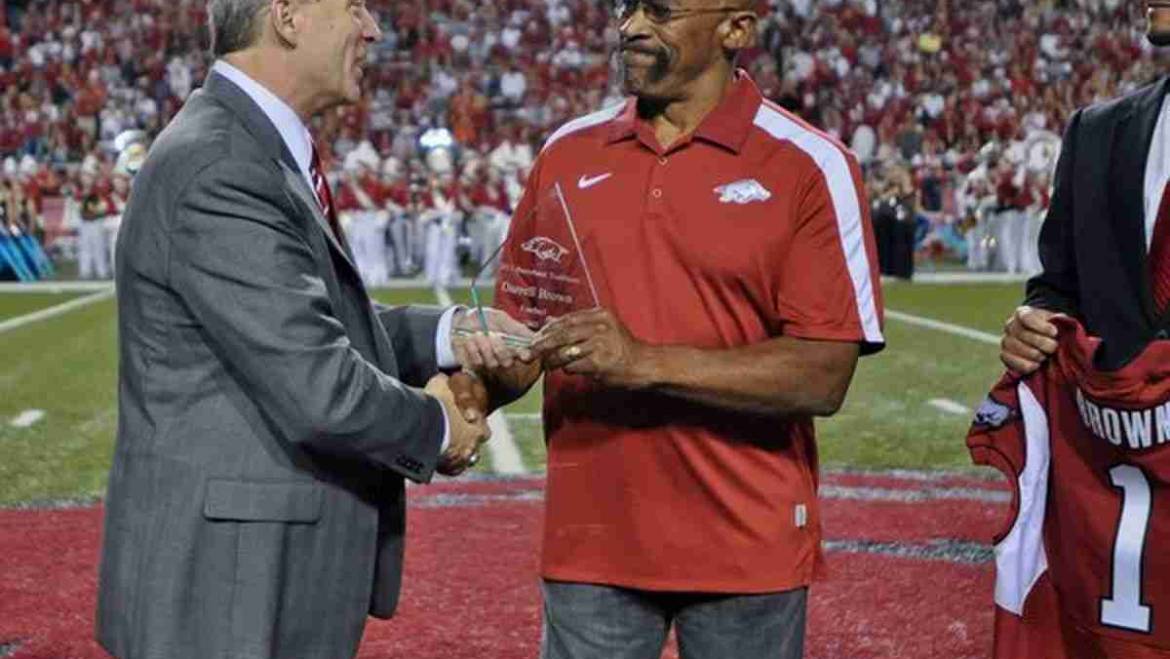

I mentioned LeVias on the ’65 SMU frosh team. He was not entirely alone since running back John Westbrook had simultaneously walked on at Baylor. Bridgers instructed his assistant coaches, including freshman coach Milburn “Catfish” Smith, to give Westbrook a fair chance. No abuse would be tolerated (observed more in the breach than in fact). There was a third gutsy black man in this drama—Darrell Brown, the least-wanted member of the Arkansas freshman team. He offered himself as a receiver and kick returner, same as LeVias. While Brown probably lacked LeVias’ athletic ability, he was scarcely allowed to show what he could do.

There seemed to be full agreement among UA administrators, coaches and players that Brown could try out, but he was to be alienated and discouraged. The coach of the 1965 Shoats (as the Arkansas freshman team was called) was Jack Davis, and he was assisted by Lon Farrell. Both of these men are deceased, and yet they deserve to be named because they permitted and facilitated some outrageous stuff. Brown was mistreated in every possible way on the football field, in the locker room and on campus. He endured racist chants from his own teammates, some of whom tried to maim him. Several times, when returning punts or kickoffs during practice, Brown’s blocking seemed to disappear and all 11 men on the other side of the ball converged on him. Injured, he scarcely survived the 1965 season before giving up his dream of being the Hogs’ first black varsity player. Now we come to Broyles and his role in this sorry tale. To what extent was he involved? Did he tell Davis and Farrell to give the interloper hell? It is quite possible that he did not but kept a hands-off approach. A wink and a nod was all it took. In doing so, Broyles let it happen and for that I am calling him to account.

Hello, ESPN?

I read what ESPN, the New York Times, the Dallas Morning News, Sports Illustrated, and USA Today said about the Boss Hog following his death. Nothing but hosannahs in the highest. I scoured them but failed to find any reference to Darrell Brown who, interestingly enough, has long since been honored and  recognized for his courageous showing in 1965. Sincere apologies have been made, as the University of Arkansas is a vastly different place today.

recognized for his courageous showing in 1965. Sincere apologies have been made, as the University of Arkansas is a vastly different place today.

Both Arkansas and Texas waited until 1970 to integrate, with running back / kick returner Jon Richardson and tight end / offensive lineman Julius Whittier, respectively. The legacies of Frank and Darrell are stained. May they rest in peace, but when I look at them I see a dearth of leadership, wisdom and vision on this crucial matter. When Royal died in 2012, none in Austin dared say a word about his reluctance to integrate. It is surely the same in Fayetteville today.

Who, then, were the Jim Crow football coaches, and how do I define the term? They had to have been at a major southern school in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and had abundant opportunities to integrate their programs but failed to do so. This is my Wall of Shame, my Hall of Dishonor: Bear Bryant (primarily Alabama), Charley McClendon (LSU), Bobby Dodd (Georgia Tech), Frank Howard (Clemson), Shug Jordan (Auburn), Johnny Vaught (Mississippi), Jess Neely (primarily Rice), Royal and Broyles. Bowden Wyatt (primarily Tennessee) retired after the 1962 season, so he gets a pass. Same for Vince Dooley, who was hired at Georgia before the 1964 season and stayed on through 1988. Like the bonafide Jim Crow coaches, however, Dooley took his sweet time in integrating.

Add Comment