Whew!! I just completed a 900-page biography of Vincent Van Gogh, the immortal Dutch post-Impressionist painter. It took me 13 days. Van Gogh / The Life, written by Steven Naifeh and the late Gregory White Smith, was published by Random House in 2011. This book, now heavily underlined and annotated, has an honored place in my library. Naifeh and Smith’s tome is impressive if for no other reason than that I did not find a single typographical error.

The prolific Van Gogh

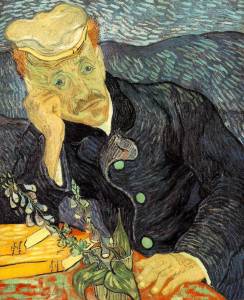

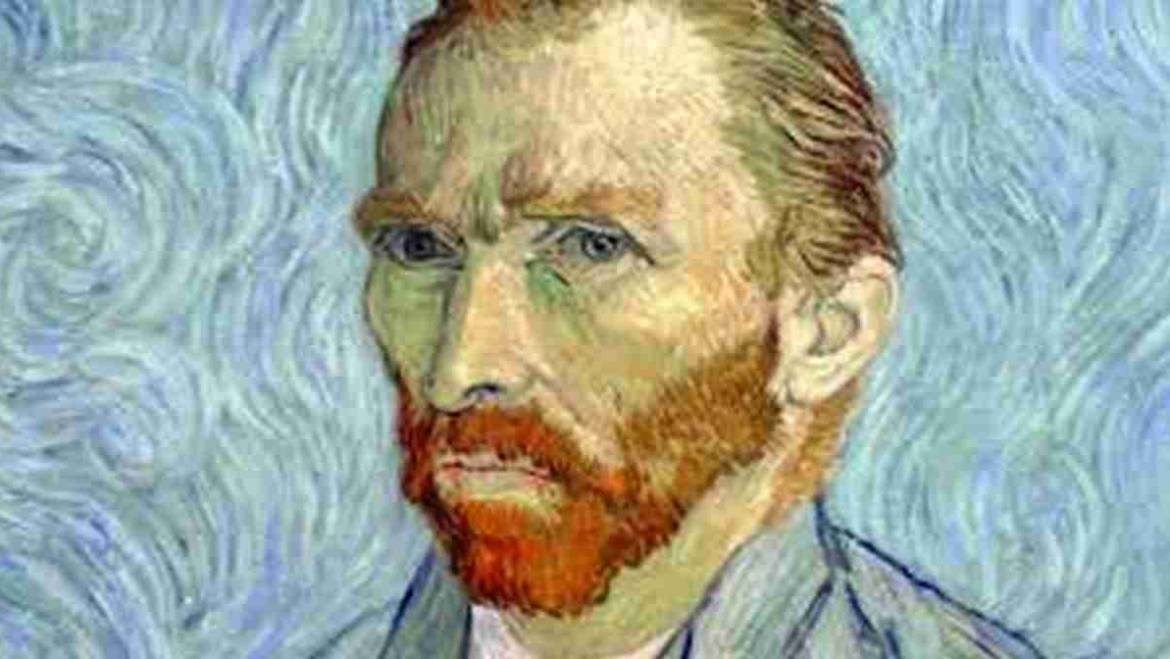

Rare is the man, woman or even child who does not know about Van Gogh (1853−1890). He is one of the biggest names in the history of Western art, having created more than 2,000 landscapes, still lifes,  portraits and self-portraits. His dramatic brushwork and bold colors were emotive and distinctive, although he sometimes employed other styles. (My art appreciation teacher at UT more than 40 years ago frowned on the use of the term “style.”) Van Gogh masterpieces include Wheatfield with Cypresses, Bedroom in Arles, The Potato Eaters, Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, Café Terrace at Night, The Yellow House, Portrait of Dr. Gachet, Irises, Sunflowers, and, of course, The Starry Night.

portraits and self-portraits. His dramatic brushwork and bold colors were emotive and distinctive, although he sometimes employed other styles. (My art appreciation teacher at UT more than 40 years ago frowned on the use of the term “style.”) Van Gogh masterpieces include Wheatfield with Cypresses, Bedroom in Arles, The Potato Eaters, Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, Café Terrace at Night, The Yellow House, Portrait of Dr. Gachet, Irises, Sunflowers, and, of course, The Starry Night.

The broad outlines of his story are also quite familiar—how he relied exclusively on the financial support of his younger brother Theo for the last 10 years of his life, when he was  learning his craft; how he met rejection from fellow artists and art dealers; how he whacked off a portion of his right ear after an argument with Paul Gauguin in December 1888; how he was institutionalized for mental illness and suffered debilitating epileptic seizures; and how he finally committed suicide in Auvers-sur-Oise, France.

learning his craft; how he met rejection from fellow artists and art dealers; how he whacked off a portion of his right ear after an argument with Paul Gauguin in December 1888; how he was institutionalized for mental illness and suffered debilitating epileptic seizures; and how he finally committed suicide in Auvers-sur-Oise, France.

NOT a suicidee

I will address that last issue right now. Naifeh and Smith make a compelling argument (and several other art scholars support them) that Van Gogh did not kill himself. A passel of young men, led by one Rene Secretan, had taunted and bullied him for weeks. Secretan borrowed a pistol from the owner of the Auberge Ravoux and either shot the troubled artist or instigated a prank that went horribly wrong. Van Gogh was almost certainly not responsible for the bullet that entered his left side (he was right-handed), although he gave conflicting answers to the investigating gendarmes before dying 30 hours after the incident.

Our Vincent was uncouth and hyperkinetic, and tended to rub people the wrong way. He yearned for interpersonal warmth but found it rarely. All too familiar with crushing loneliness and rejection, he frequented bordellos in The Hague, London, Dordrecht, Brussels, Antwerp, Amsterdam, Paris, Arles and elsewhere. Beginning in 1880, he labored furiously on his art, churning out paintings that few people wanted to see, much less buy. Only one of his works, The Red Vineyard, was purchased in his life. Often he predicted to Theo that his paintings would someday be recognized and of value. H.G. Tersteeg had a different opinion. Tersteeg, a prominent art dealer in Paris, tired of Van Gogh’s constant importunings and told him that he had no talent whatsoever. But guess what? The tide was about to turn. A Van Gogh painting was featured in a major exhibition in Brussels. Soon thereafter, a critic named Albert Aurier wrote an ecstatic review that made Van Gogh a figure to be reckoned with in Parisian intellectual circles. His star was ascending just when he died.

Fame beyond imagining

Thanks in large part to the work of his sister-in-law Johanna Bonger-Van Gogh, the voluminous exchange of letters between Vincent and Theo was cataloged and made public. Such a poignant story of struggle and brotherly love! By the turn of the century, Van Gogh’s fame spread from his native Holland and France to Germany, the rest of Europe and across the Atlantic. Van Gogh exhibitions were mounted, and the value of those once-scorned paintings climbed: Irises went for $54 million in 1987, Portrait of Dr. Gachet was auctioned for $82.5 million in 1990, and The Starry Night (property of the Museum of Modern Art in New York since 1941) would fetch more than $300 million if put up for sale.

was auctioned for $82.5 million in 1990, and The Starry Night (property of the Museum of Modern Art in New York since 1941) would fetch more than $300 million if put up for sale.

Van Gogh’s fame only rose as the years passed. The 1934 biographical novel Lust for Life by Irving Stone contributed to it, as did the 1956 film of the same name (starring a much-too-handsome Kirk Douglas). Today there are plaques at most of the 30 addresses where Van Gogh lived in Holland, Belgium, England and France. The eatery that he painted in Arles is now Café Van Gogh. His last residence, upstairs at the Auberge Ravoux, is known as the Van Gogh Room. It was opened to the public in 1993 and has had more than 1 million visitors. By the same token, long lines of people wait outside daily to enter the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam—as big as a U.S. presidential library. Don McLean’s 1971 song “Vincent” did nothing to hurt the long-deceased painter’s popularity.

Some skeptics

And yet not everybody is convinced. Van Gogh has his detractors, no doubt about it. Some hold that the “tortured genius” theme led to an inflated valuation of his work. Moreover, his inability to accurately capture faces and figures is undeniable; Van Gogh lamented this himself. Critics blast him for having thrown paint on canvasses indiscriminately and working too rapidly; he once bragged to Theo of having completed a painting in under an hour. I am not about to pretend that I know art any more than I do classical music, economic theory or how to speak the Serbo-Croatian dialect, for that matter. I am a dilettante, but in liking Van Gogh’s art I have lots of company. I would also point out that B.B. King, Bob Dylan, John Lennon and Johnny Cash were not technically “great” guitarists. But whoever tries to assert that those gentlemen did not make serious musical contributions is more insane than Vincent Van Gogh ever was.

Add Comment