I’m trying to think what I was doing in 1988. I was living on Lafayette Street in east Austin, working as a proofreader at G&S Typesetters, writing a weekly column for the American-Statesman and preparing to run my first marathon. It was also the year I sent a letter to a certain New Jersey senator, William Warren “Bill” Bradley. Dismayed by two terms of Ronald Reagan, I urged him to mount a campaign for the presidency. I soon got a response. Bradley thanked me for the nice words I had said about him but indicated that he still had work to do in the Senate. Twelve years later, he would seek the highest office in the land and fail completely. I thought then, and still do, that Bradley might have made an excellent president.

He becomes a Tiger

Few have combined the roles of scholar and jock as well as Bradley, a native of Crystal City, Missouri. He reached his full height of 6’5″ when he was just 15 years old and thus gravitated toward basketball. He chose Princeton over Duke in 1961 not because it would better prepare him for “the league” but  because he had his eye on politics or diplomatic work after he quit playing hoops. Thinking about life after sports while still in high school—this was a mature young man indeed.

because he had his eye on politics or diplomatic work after he quit playing hoops. Thinking about life after sports while still in high school—this was a mature young man indeed.

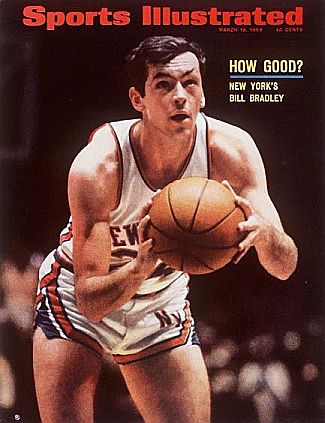

Bradley was a star from the get-go, scoring 30 points per game as a freshman. In three years with the Tigers varsity, he rang the bell for 2,503 points. The youngest member of the U.S. Olympic gold-medal-winning team in 1964, he led Princeton to the Final Four in ’65 and scored 58 points in a losing effort against Michigan. (The 1965 Tigers were among the last all-European-American teams to reach the Final Four; Kentucky and Duke in ’66 were the penultimate and Dean Smith’s UNC Tar Heels in ’67 have the “honor” of being the last.)

Court vision

Consensus all-American and player of the year in 1965, Bradley was a media darling. He was intelligent, articulate and humble, and never big-timed it among his coaches and teammates. I suspect there was a bit of racism, conscious or otherwise, involved in sports writers fawning all over him since Bradley excelled despite being relatively slow and no great leaper. He never threw down a monster dunk, a real in-yo-face-disgrace rim-wrecker. He hit a high percentage of shots when left open, but he could not “create” them. Nor was his defense anything to write home about. Nevertheless, Bill Bradley could hoop. He dribbled and passed well, and he made free throws with monotonous regularity. He was a team player. Most of all, however, he had court vision—that is, he could see things happening before they happened. Court vision is very hard to develop; either you have it or you don’t. This crucial trait was shared by Larry Bird of the Boston Celtics. (More currently, Rajon Rondo of the Chicago Bulls, Chris Paul of the Los Angeles Clippers, Kyrie Irving of the Cleveland Cavaliers, Marc Gasol of the Memphis Grizzlies and Ben Simmons of the Philadelphia 76ers are also recognized as being blessed with court vision.)

Drafted by the New York Knicks, Bradley went instead to England. His magna cum laude degree from Princeton had won him a Rhodes scholarship. He studied politics, economics and philosophy at the University of Oxford, and then dropped out two months prior to graduation to join the U.S. Air Force Reserves. This, in truth, was a way to dodge the draft, as the Vietnam War was getting hotter by the  moment. When Bradley first put on a Knicks uniform in early 1968, he had been away from high-level competition for more than two years and did not dazzle anybody at first. But he was a solid contributor for 10 seasons and helped the Knicks win NBA titles in 1970 and 1973, retiring with 9,217 points, 2,354 rebounds and 2,533 assists. He never led the league in any statistical category, even free-throw shooting, which I find surprising since he hit 84% of his shots from the charity stripe.

moment. When Bradley first put on a Knicks uniform in early 1968, he had been away from high-level competition for more than two years and did not dazzle anybody at first. But he was a solid contributor for 10 seasons and helped the Knicks win NBA titles in 1970 and 1973, retiring with 9,217 points, 2,354 rebounds and 2,533 assists. He never led the league in any statistical category, even free-throw shooting, which I find surprising since he hit 84% of his shots from the charity stripe.

Budding politician

An atypical pro basketball player, he read books without pictures. He visited museums and partook of cultural events when on the road. As a good liberal, he delved into social and political issues. In one off-season, Bradley worked in the Office of Economic Opportunity in Washington, D.C. He also taught at some street academies in Harlem. During his last four years with the Knicks, he helped various Democratic candidates with their political campaigns.

Bradley was no fool. He knew what name recognition was and that he had lots of it. Furthermore, he was tall, handsome and personable, and could speak with some degree of authority about both domestic and international issues. His old Princeton coach, Butch Van Breda Kolff, once predicted that he would become the governor of Missouri. Not quite. In 1978, Bradley was elected as one of New Jersey’s senators, a seat he held for 18 years. It was during this time that I wrote and urged him to consider moving up, and in the USA there is only one higher elective office—the POTUS. He demurred, as you know. Bradley left the Senate in 1997 rather publicly, stating that “politics is broken.”

Just three years later, he had a change of heart. Although his record in the Senate was rather spotty, some key people in the Democratic Party backed him, donors wrote big checks, and the media lavished attention on his campaign; Time magazine gave him a cover story. Bradley claimed to have a “new vision” for America. His early poll numbers were good, but when the primaries started he faltered, as his campaign was inept and lacked direction. Perhaps the biggest problem was that Bradley’s style of public speaking was bland, flat and uninspiring. By March 2000, he had withdrawn and endorsed Al Gore (who went on to lose a contentious election to the Republicans’ George W. Bush).

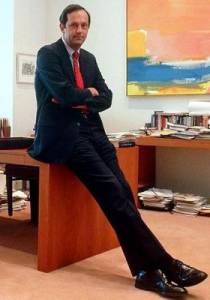

These days, he is a consultant and investment banker, and sits on the boards of several large companies. Befitting a man who was once an Eagle Scout and taught Sunday School at a Presbyterian church in Crystal City, he does some volunteer and non-profit work. He is also chairman of a fund that seeks to reduce world poverty. OK, he never got to the White House and is certainly not one of basketball’s all-time greats. But I am hard-pressed to name another jock who penned seven nonfiction books without the help of a ghostwriter.

Add Comment