More than 40 years after the demise of the American Basketball Association, you can still color me red, white and blue—as in the league’s rather garish ball. During my junior year of high school, I considered myself lucky to witness the arrival of Spencer Haywood. This 6′ 9″ forward for the Denver Rockets had played just one season of college ball (at the University of Detroit), but he set the ABA on fire with 30 points and 19 rebounds per game in 1970. I raved about Haywood and called him among the best players in the world, and that certainly included the NBA. Two years later, however, my brother Randy went to see our Dallas Chaparrals play the Virginia Squires. He opined rather boldly that this team from the Old Dominion had a rookie, Julius Erving, who was even better. Better than Haywood! I was skeptical, but I made sure to see the Chaps and Squires at Moody Coliseum circa February 1972.

An electrifying player

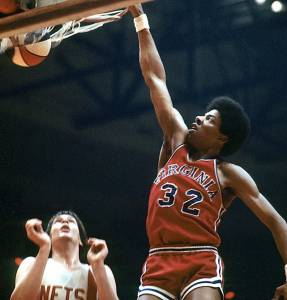

I have no clear memory of who won the game or what kind of numbers Erving put up. But Randy’s hoops acumen was borne out. Not that he was alone, because fans, reporters, coaches and announcers had much the same opinion: The 6′ 7″ forward with the sweet nickname of “Doctor J” could run the floor like a gazelle and jump through the rafters. He was a ferocious rebounder and had acrobatic moves that made defenders scream for mercy. His hands resembled meat hooks, allowing him to control the ball with the greatest of ease and go up for some of the most astounding dunks you ever saw. Although Erving averaged 27 and 16, a bit below what Haywood had done two years before with Denver, no self-respecting basketball historian would mention the two men in the same breath. Haywood—who had punched a ref while at Detroit—jumped to the NBA’s Seattle SuperSonics the next season despite having a valid contract with the Rockets. He played for five franchises, became addicted to cocaine and gained a reputation as a loafer who bad-mouthed coaches and teammates alike. And Erving? He, too, wanted to play in the NBA and signed with the Atlanta Hawks, but a three-judge panel said he belonged to the Squires who paid him a miserly $125,000 per year.

like a gazelle and jump through the rafters. He was a ferocious rebounder and had acrobatic moves that made defenders scream for mercy. His hands resembled meat hooks, allowing him to control the ball with the greatest of ease and go up for some of the most astounding dunks you ever saw. Although Erving averaged 27 and 16, a bit below what Haywood had done two years before with Denver, no self-respecting basketball historian would mention the two men in the same breath. Haywood—who had punched a ref while at Detroit—jumped to the NBA’s Seattle SuperSonics the next season despite having a valid contract with the Rockets. He played for five franchises, became addicted to cocaine and gained a reputation as a loafer who bad-mouthed coaches and teammates alike. And Erving? He, too, wanted to play in the NBA and signed with the Atlanta Hawks, but a three-judge panel said he belonged to the Squires who paid him a miserly $125,000 per year.

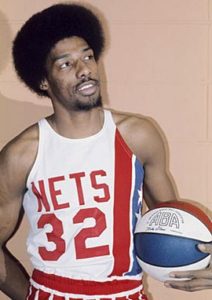

Doc spent five seasons in the ABA—two with Virginia and three with the New York Nets, a franchise to which he had offered himself after two years of varsity ball at the University of Massachusetts. (Pardon the digression, but Erving was born and raised on Long Island which is not usually thought of as a basketball hotbed. He stood just 6′ 3″ upon graduation from high school and was lightly recruited. Nevertheless, he flourished in Amherst, averaging 26 points and 20 rebounds per game. That did a lot  for his reputation, along with playing well in the Rucker Park tourney in Harlem and a pre-Olympics tour with other collegians.) The Nets played their home games at the Nassau Coliseum. Not big time? Consider that Erving’s Squires were a regional team playing at the Norfolk Scope, Roanoke Civic Center, Richmond Coliseum and Hampton Coliseum. None of those venues are to be confused with Madison Square Garden. When people say the ABA was bush league, this is what they mean.

for his reputation, along with playing well in the Rucker Park tourney in Harlem and a pre-Olympics tour with other collegians.) The Nets played their home games at the Nassau Coliseum. Not big time? Consider that Erving’s Squires were a regional team playing at the Norfolk Scope, Roanoke Civic Center, Richmond Coliseum and Hampton Coliseum. None of those venues are to be confused with Madison Square Garden. When people say the ABA was bush league, this is what they mean.

Carrying the ABA

Erving led the Nets to ABA titles in 1974 and 1976, by which time he was widely recognized as the game’s greatest player. In the playoffs of the latter season, I went to San Antonio to see the Nets and Spurs in a semifinal game. I can tell you, HemisFair Arena was packed and rocking that night. Erving was sublime—an athletic man in full.

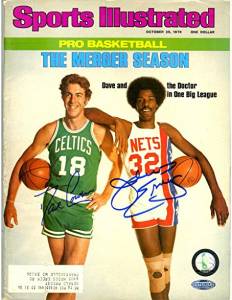

He had carried the ABA for its last three seasons and was the main reason for the merger by which the Nets, Spurs, Rockets/Nuggets and Indiana Pacers entered the NBA. He posed for the cover of Sports Illustrated with Dave Cowens of the Boston Celtics as a new era of pro hoops began. Soon thereafter, he  was traded to the Philadelphia 76ers. Although still a tremendous player, Erving’s peak had passed. His knees constantly ached, he could not sky quite like before, and he was facing tougher defenses. Philly reached the NBA finals in 1977, 1980 and 1982, and he was the league MVP in ’81. When the Sixers finally won the championship in 1983, Moses Malone was their top guy and arguably Charles Barkley was No. 2. Erving was the third-best player on his team, a fact he seemed to handle gracefully.

was traded to the Philadelphia 76ers. Although still a tremendous player, Erving’s peak had passed. His knees constantly ached, he could not sky quite like before, and he was facing tougher defenses. Philly reached the NBA finals in 1977, 1980 and 1982, and he was the league MVP in ’81. When the Sixers finally won the championship in 1983, Moses Malone was their top guy and arguably Charles Barkley was No. 2. Erving was the third-best player on his team, a fact he seemed to handle gracefully.

Doc and Mike—much in common

He was not, however, especially graceful about the young man who purported to have taken his place as the alpha dog of pro basketball. I refer to Michael Jordan of the Chicago Bulls. They were essentially the same size, could play in the front or back court, and were talented and competitive in the extreme. Their NBA careers overlapped from 1985 through 1987. In Doc’s last year, he was still competent but knew it was time to go. Jordan, by contrast, averaged a whopping 37 points per game. (In Jordan’s final year, 2003, Kobe Bryant was scoring 30 ppg for the Lakers; the torch had been passed once again.)

This is not the time or place to compare Erving and Jordan (much less Jordan and Bryant), but let’s just say they were among the best to ever lace up a pair of high-tops. One other thing they have in common is that they have worked as NBA executives—Erving with the Orlando Magic and Jordan with the Washington Wizards and Charlotte Hornets—and done rather poorly.

Erving, who today sports a head of gray hair, plays golf, gives interviews and indulges himself in the retired-sports-celebrity lifestyle. In fact, there’s trouble in paradise. He impregnated a European-American female sports writer when he was with Philly (and denied the existence of his love child for 27 years), went through a bitter and costly divorce, lost $5 million on a failed golf course, saw his Utah home foreclosed and in 2011 had to auction more than 100 pieces of memorabilia including his championship rings with the ’74 and ’76 Nets, and ’83 Sixers. Both of his sons had drug problems and were incarcerated, and one of them, 19-year-old Cory, died in Florida after driving his car into a lake.

Add Comment