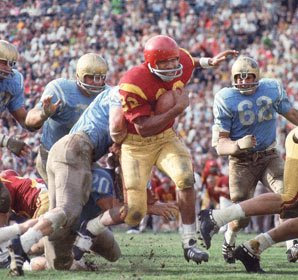

Exactly 50 years have passed since the 1967 college football season. I was a ninth-grader at Hill Junior High School in Dallas, growing up but still quite immature. That, I believe, helps explain why I was so enthralled with the showing of a particular player out on the West Coast. The reference is to O.J. Simpson of the University of Southern California. I read about him, saw him on television and heard  commentary. He had silky moves and was able to run 100 yards in 9.4 seconds. He could read his blocks, hesitate briefly and turn on the jets. Simpson, to my eyes, was the most dazzling running back ever. His 64-yard touchdown run in the closing minutes of the Trojans’ 21-20 defeat of No. 1 UCLA was an iconic play. Southern Cal won the national crown in 1967, and only a Rose Bowl loss to Ohio State prevented them from repeating in ’68. Nevertheless, “the Juice” was soon wearing a tuxedo and making an acceptance speech at New York’s Downtown Athletic Club as the 34th winner of the Heisman Trophy.

commentary. He had silky moves and was able to run 100 yards in 9.4 seconds. He could read his blocks, hesitate briefly and turn on the jets. Simpson, to my eyes, was the most dazzling running back ever. His 64-yard touchdown run in the closing minutes of the Trojans’ 21-20 defeat of No. 1 UCLA was an iconic play. Southern Cal won the national crown in 1967, and only a Rose Bowl loss to Ohio State prevented them from repeating in ’68. Nevertheless, “the Juice” was soon wearing a tuxedo and making an acceptance speech at New York’s Downtown Athletic Club as the 34th winner of the Heisman Trophy.

Biggest fan of No. 32

He had plenty of fans, but nobody loved him more than I. Watching O.J. Simpson carry a football was a sort of athletic rapture. I followed his movement into the pros. He played 11 seasons (nine with the Buffalo Bills and two with his hometown San Francisco 49ers), gaining 11,236 yards and scoring 76  touchdowns. He led the NFL in rushing four times and was the first player to gain more than 2,000 yards in a season, in 1973. Simpson reached the playoffs just once, as the Bills lost to Pittsburgh on December 22, 1974. His numbers—and ability—went down at the end; it happens even to the greatest. I actually thought Simpson handled himself well by spending nine years in snowy Buffalo, not exactly the most desired destination in the NFL.

touchdowns. He led the NFL in rushing four times and was the first player to gain more than 2,000 yards in a season, in 1973. Simpson reached the playoffs just once, as the Bills lost to Pittsburgh on December 22, 1974. His numbers—and ability—went down at the end; it happens even to the greatest. I actually thought Simpson handled himself well by spending nine years in snowy Buffalo, not exactly the most desired destination in the NFL.

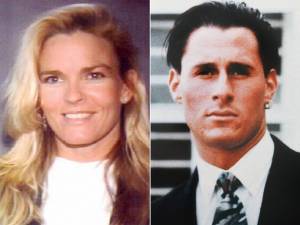

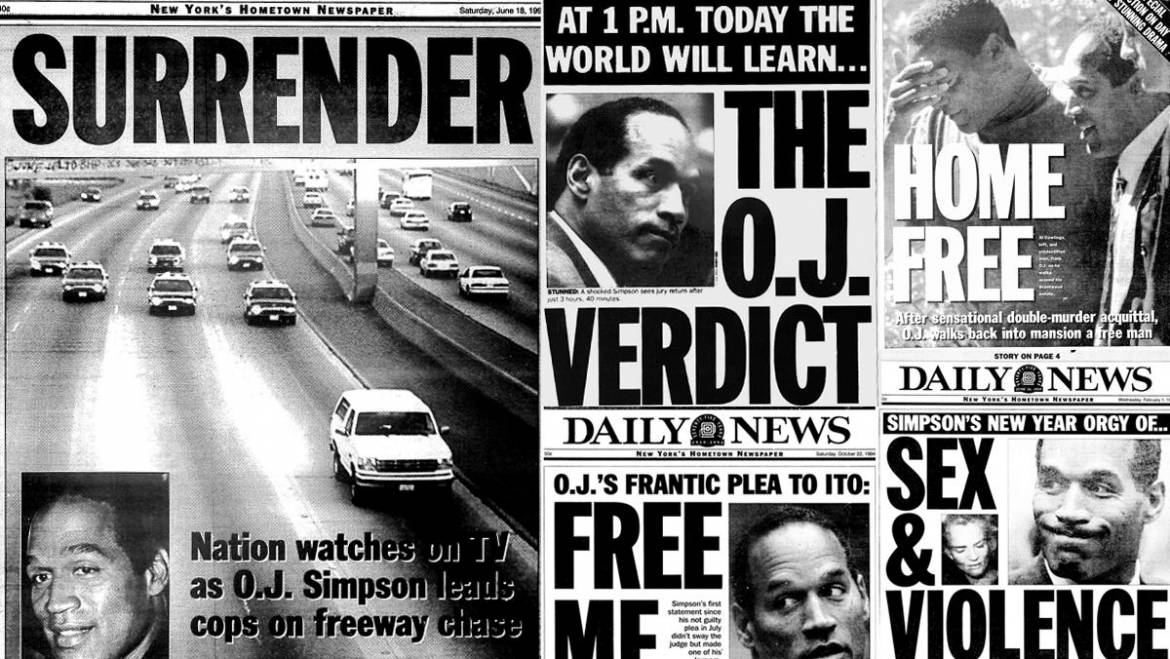

After that, of course, he was a popular actor (Naked Gun, Towering Inferno), commercial pitchman (Hertz Rent-A-Car) and announcer (Monday Night Football). He had a well-crafted image as a nice guy, an amiable guy, a non-threatening guy. Then came the June 12, 1994 murders of his estranged wife Nicole Brown and her friend Ronald Goldman. Both were slashed and stabbed to death outside her condo in Los Angeles’ Brentwood district. The slow-speed chase of a semi-suicidal Simpson and his friend and former Trojans teammate Al Cowlings in a white Ford Bronco is part of American  lore. Following a nine-month trial, he won acquittal in October 1995. The jury was made up of nine blacks, one Hispanic and two European-Americans. Also pertinent to the case is the fact that Simpson was black and his two victims were European-American. The jurors’ decision was, of course, a travesty. Some of the black jurors later as much as admitted that they had voted to acquit as some kind of historical payback: The legal system was stacked against them for a long time, and so they had taken the opportunity to subvert things. Racial identification had trumped justice.

lore. Following a nine-month trial, he won acquittal in October 1995. The jury was made up of nine blacks, one Hispanic and two European-Americans. Also pertinent to the case is the fact that Simpson was black and his two victims were European-American. The jurors’ decision was, of course, a travesty. Some of the black jurors later as much as admitted that they had voted to acquit as some kind of historical payback: The legal system was stacked against them for a long time, and so they had taken the opportunity to subvert things. Racial identification had trumped justice.

A painful verdict

I was pained by the verdict since it was clear that Simpson had hacked Brown and Goldman, a couple of vibrant young European-Americans, to death; Brown’s head was almost severed from her body. My intense admiration of Simpson, needless to say, vanished the moment the jury foreman made the announcement. Simpson, attorney Johnnie Cochran and the rest of his legal team walked out of the courtroom wearing big smiles. He vowed to do his best to find “the real killers” and bring them to justice.

It infuriates me to read of or hear references to this killer as “O.J.,” as if he were some cuddly teddy bear. Few things make me scream louder.

A couple of months after I left Austin for Daegu, I was sitting in a McDonald’s with a Korean friend. He saw a black guy go by, and that was reason enough for him to opine that blacks thought Simpson was innocent but European-Americans felt otherwise. I told him, “A very large mountain of circumstantial and factual evidence (the DNA most of all) indicated that Simpson committed those murders, and whoever wants to refute it is free to try.” I also pointed out that at least a few blacks were able to ignore the pull of neo-racism and state the plain truth.

Not much justice, but some

In 1997, a civil trial came to a conclusion quite different from what had been rendered in 1995. Simpson was found liable for the wrongful deaths of Brown and Goldman, and ordered to pay $33.5 million, although less than $1 million was ever extracted. He was kicked out of the estate he had lived in for 20 years and had minor legal problems but managed to earn enough money from signing autographs to live. So what if he was a pariah? Hey, he was free! While Brown and Goldman were moldering in their graves, Simpson was playing golf in Florida and chasing skanky girls.

He screwed up in September 2007 when he and a group of armed men busted into a Las Vegas hotel room and confiscated a load of sports memorabilia—items Simpson claimed belonged to him. He was  found guilty of all charges (criminal conspiracy, kidnapping, assault, robbery and using a deadly weapon) and sentenced to 33 years in prison with the possibility of parole in nine. The Nevada Supreme Court affirmed his conviction, and he was remanded to Lovelock Correctional Center and given inmate ID number 1027820. He lives in a two-man cell, sharing a bunk bed, toilet and sink. His work shift, four days a week, consists of mopping floors and cleaning equipment in the prison’s gym. My least-favorite jailbird shows signs of Alzheimer’s disease or chronic traumatic encephalopathy from his long-ago football career. He suffers from headaches and blurry vision, and often stutters when he speaks.

found guilty of all charges (criminal conspiracy, kidnapping, assault, robbery and using a deadly weapon) and sentenced to 33 years in prison with the possibility of parole in nine. The Nevada Supreme Court affirmed his conviction, and he was remanded to Lovelock Correctional Center and given inmate ID number 1027820. He lives in a two-man cell, sharing a bunk bed, toilet and sink. His work shift, four days a week, consists of mopping floors and cleaning equipment in the prison’s gym. My least-favorite jailbird shows signs of Alzheimer’s disease or chronic traumatic encephalopathy from his long-ago football career. He suffers from headaches and blurry vision, and often stutters when he speaks.

It’s not the same as being found guilty for murdering Brown and Goldman, but at least he is incarcerated. I have lots of compassion in my heart but none for Simpson, whom I once revered. He is doing hard time and now suffers the humiliation of being incontinent. Yes, the Juice is loose. Having lost control of his bowels, he must wear adult diapers. Other inmates at Lovelock sometimes call him “Stinky.”

Add Comment