Nobody ever said that running a big-time football program is easy. You have to deal with pushy alumni, egg-heads on the faculty who want to abolish intercollegiate athletics and know-it-all reporters at the local newspaper, not to mention keeping your players academically eligible and staying off the NCAA’s watch-list. The main thing you must do, however, is win. You gotta win ball games and better yet championships if you want to remain the guy with the most prestigious job on campus. Not to exaggerate, but if you win all else is forgiven. And the key to winning is recruiting—convincing high school boys with good football skills to enroll at your university and not those of your competitors. An effective recruiter is hands-down more valuable than a smooth media operator, a coach who placates the alums or an X’s and O’s guy. No coach would knowingly shut his eyes to a segment of the population with, arguably, the most athletic talent. But that’s exactly what was done by coaches at the major universities in the South in the 1950s, 1960s and in a few cases the early 1970s. These fellows seemed to have a dispensation that permitted them to ignore the black players who then attended segregated high schools. Winning took a back seat to maintenance of the prevailing Jim Crow racial mores.

The existence of a “gentlemen’s agreement” among Southern coaches during those years can hardly be doubted. Obviously no document was written up, signed, notarized and filed at the county courthouse in Dallas, Gainesville, Winston-Salem and other places. But whether spoken or unspoken, this deal was understood and adhered to by every coach in the Southwest Conference, Southeastern Conference and Atlantic Coast Conference. It would have taken a strong man, a man with direction and purpose, to buck his fellow coaches, school president and conservative-minded boosters (especially if they were donors). What’s a college football coach, though, if he’s not a leader? A leader says, “We’re going this way. Follow me.”

I have chosen eight coaches—all members of the College Football Hall of Fame—who deserve to be taken to the woodshed for their failure to confront the crucial matter of racial integration when they had the chance. Each would have had a far greater legacy if he bitten the proverbial bullet rather than dither, make excuses or stonewall.

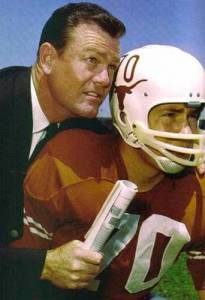

• Darrell Royal (Texas). I will not cut my alma mater any slack. UT was one of the last schools to have a black player on its varsity football team—offensive lineman/tight end Julius Whittier, in 1970—and Royal is why. I knew him, interviewed him numerous times, liked him and admired him, but the truth is that he simply would not act. The years went by in Austin, and DKR’s Longhorns remained all-white. Mel Farr, Bubba Smith, Warren McVea and other excellent black players wanted to come to UT, but he feigned disinterest; he told Smith (twice all-America at Michigan State and No. 1 pick in the 1967 NFL draft) that he was free to try out. Royal’s inability or refusal to move is my main reason for opposing the renaming of Memorial Stadium after him in 1997. Let’s give credit to E.A. Curry and Robinson Parsons who were walk-ons with the 1967 freshman team and Talmadge Bluiett with the ’68 frosh. Since they had the gumption to do that, Royal should have found a way to get them on the varsity.

• Darrell Royal (Texas). I will not cut my alma mater any slack. UT was one of the last schools to have a black player on its varsity football team—offensive lineman/tight end Julius Whittier, in 1970—and Royal is why. I knew him, interviewed him numerous times, liked him and admired him, but the truth is that he simply would not act. The years went by in Austin, and DKR’s Longhorns remained all-white. Mel Farr, Bubba Smith, Warren McVea and other excellent black players wanted to come to UT, but he feigned disinterest; he told Smith (twice all-America at Michigan State and No. 1 pick in the 1967 NFL draft) that he was free to try out. Royal’s inability or refusal to move is my main reason for opposing the renaming of Memorial Stadium after him in 1997. Let’s give credit to E.A. Curry and Robinson Parsons who were walk-ons with the 1967 freshman team and Talmadge Bluiett with the ’68 frosh. Since they had the gumption to do that, Royal should have found a way to get them on the varsity.

• Bear Bryant (Alabama). They called it “the heart of Dixie” for good reason. Montgomery was the original capitol of the Confederacy, Bull Connor used dogs and water cannons on civil rights protesters in Birmingham, George Wallace stood in UA’s schoolhouse door, state troopers brutalized black citizens at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma and so on. Racism was deeply entrenched in Alabama, I realize that. And yet Bryant, respected and revered by almost every white citizen in the state, could have insisted on integrating the Crimson Tide football program. Had he done so, he would have prevailed and others would have gotten in line. Defensive lineman John Mitchell and running back Wilbur Jackson integrated the Alabama squad in 1971, although Dock Rone, Andrew Pernell, Art Dunning, Melvin Leverett and Jerome Tucker were gutsy walk-ons with the 1967 freshman team.

• Frank Broyles (Arkansas). His career parallels that of Royal in many ways; he got to Fayetteville in 1958, whereas Royal started at UT a year earlier, and they retired after the Horns and Hogs faced off one night in 1976. Royal was a caretaker athletic director, but Broyles did far more in that role over a 33-year span. Running back Jon Richardson (1970) has the honor of being the first black player on the Arkansas varsity, but maybe he shouldn’t have been. Darrell Brown, a walk-on with the freshman team in 1965, was subjected to malicious treatment by coaches and fellow players. Injured, isolated and discouraged, he never made it to the varsity. If Broyles had been wise—and had a heart—he would have ensured that the young man get a fair shot to become a Razorback, same as his white peers. What happened to Darrell Brown was one of the most shameful episodes in University of Arkansas history.

• Frank Broyles (Arkansas). His career parallels that of Royal in many ways; he got to Fayetteville in 1958, whereas Royal started at UT a year earlier, and they retired after the Horns and Hogs faced off one night in 1976. Royal was a caretaker athletic director, but Broyles did far more in that role over a 33-year span. Running back Jon Richardson (1970) has the honor of being the first black player on the Arkansas varsity, but maybe he shouldn’t have been. Darrell Brown, a walk-on with the freshman team in 1965, was subjected to malicious treatment by coaches and fellow players. Injured, isolated and discouraged, he never made it to the varsity. If Broyles had been wise—and had a heart—he would have ensured that the young man get a fair shot to become a Razorback, same as his white peers. What happened to Darrell Brown was one of the most shameful episodes in University of Arkansas history.

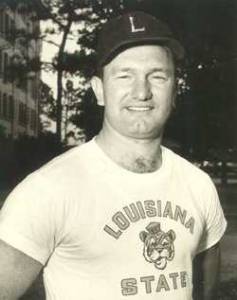

• Charlie McClendon (LSU). Lots of athletic talent in Louisiana, and LSU is the only major school in the state. Jolly Cholly ran the program from 1962 to 1979, and won but a single SEC championship. Running back Lora Hinton and defensive back Mike Williams were the first black Tigers in 1972. This is indefensible, especially since federal courts had mandated full integration of the university in 1964. For what it’s worth, the 2016 LSU team is 84% black.

• Charlie McClendon (LSU). Lots of athletic talent in Louisiana, and LSU is the only major school in the state. Jolly Cholly ran the program from 1962 to 1979, and won but a single SEC championship. Running back Lora Hinton and defensive back Mike Williams were the first black Tigers in 1972. This is indefensible, especially since federal courts had mandated full integration of the university in 1964. For what it’s worth, the 2016 LSU team is 84% black.

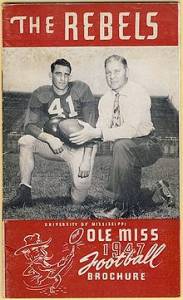

• Johnny Vaught (Mississippi). I am not about to pretend that integrating at Ole Miss was going to be easy or quick. This state has long been the poorest in the union and is synonymous with slavery, racism and the Ku Klux Klan. Of course, 1962 is the year James Meredith enrolled at Ole Miss, sparking an on- campus riot that left two dead and more than 300 injured. The Rebels went 10-0 and finished third in the nation, helping to assuage that scene; Vaught liked to say that in so doing, his team had “saved Mississippi.” Fans claimed that the Rebs deserved to be named national champs, but consider that those 10 games took place in Oxford, Jackson, Memphis, Baton Rouge, Knoxville and New Orleans—hardly a national schedule. Vaught retired in 1970, his 24th season at Mississippi, having never coached a single black player. However, he was called back to the sidelines in the middle of the 1973 season when Billy Kinard was fired. Defensive end Ben Williams had integrated the team the previous year.

campus riot that left two dead and more than 300 injured. The Rebels went 10-0 and finished third in the nation, helping to assuage that scene; Vaught liked to say that in so doing, his team had “saved Mississippi.” Fans claimed that the Rebs deserved to be named national champs, but consider that those 10 games took place in Oxford, Jackson, Memphis, Baton Rouge, Knoxville and New Orleans—hardly a national schedule. Vaught retired in 1970, his 24th season at Mississippi, having never coached a single black player. However, he was called back to the sidelines in the middle of the 1973 season when Billy Kinard was fired. Defensive end Ben Williams had integrated the team the previous year.

• Frank Howard (Clemson). Thirty years as the Tigers’ head coach was enough time for Howard to put his stamp forever on the program. This guy was an overt racist who often said the “N” word: never. Never would Clemson so much as play against an integrated team (wrong—the Tigers met Oklahoma in Norman on September 21, 1963 and lost, 31-14), never would a black player be allowed to enter Memorial Stadium (wrong again—Darryl Hill of Maryland did so on November 16, 1963*) and never, never, never would one don an orange Clemson uniform (also wrong—it finally happened in 1971 when defensive back Marion Reeves took the field with his teammates, two years after Howard retired**). The bull-headed, bald-headed coach had changed his tune by the mid-1970s: “I wanted to integrate, but they would have rode [sic] me out of town on a rail.”

was an overt racist who often said the “N” word: never. Never would Clemson so much as play against an integrated team (wrong—the Tigers met Oklahoma in Norman on September 21, 1963 and lost, 31-14), never would a black player be allowed to enter Memorial Stadium (wrong again—Darryl Hill of Maryland did so on November 16, 1963*) and never, never, never would one don an orange Clemson uniform (also wrong—it finally happened in 1971 when defensive back Marion Reeves took the field with his teammates, two years after Howard retired**). The bull-headed, bald-headed coach had changed his tune by the mid-1970s: “I wanted to integrate, but they would have rode [sic] me out of town on a rail.”

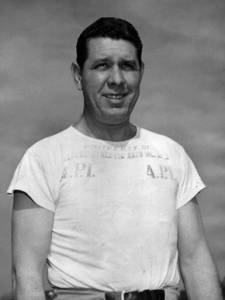

• Shug Jordan (Auburn). His career as head coach at Auburn is almost as long (25 years) as Howard’s over at Clemson. Jordan is rightfully thought of as one of those old-school men who grimaced when the topic of integration was raised. And yet he signed running back James Owens in 1969, making Auburn the first Deep South school to have taken that fateful step. Owens played two seasons, 1971 and 1972, for the Tigers.

• Shug Jordan (Auburn). His career as head coach at Auburn is almost as long (25 years) as Howard’s over at Clemson. Jordan is rightfully thought of as one of those old-school men who grimaced when the topic of integration was raised. And yet he signed running back James Owens in 1969, making Auburn the first Deep South school to have taken that fateful step. Owens played two seasons, 1971 and 1972, for the Tigers.

• Vince Dooley (Georgia). Perhaps it’s odd to have Dooley on this list since he did not get the UGA head coaching gig until 1964. He was younger than the other seven (in fact, he is the only one still living), but that did not mean his views were especially progressive. The Bulldogs won SEC titles in 1966 and 1968, but they were just 5-5 in 1970, so Dooley rolled the dice by signing five black players: receiver Richard Appleby, running back Horace King, defensive lineman Chuck Kinnebrew, linebacker Clarence Pope and defensive back Larry West. This was just a decade after the university got a court order to integrate, sparking a violent response from 200 white students. Dooley retired after the 1988 season with 201 victories, although he stayed on as AD until 2004.

that did not mean his views were especially progressive. The Bulldogs won SEC titles in 1966 and 1968, but they were just 5-5 in 1970, so Dooley rolled the dice by signing five black players: receiver Richard Appleby, running back Horace King, defensive lineman Chuck Kinnebrew, linebacker Clarence Pope and defensive back Larry West. This was just a decade after the university got a court order to integrate, sparking a violent response from 200 white students. Dooley retired after the 1988 season with 201 victories, although he stayed on as AD until 2004.

* In pre-game warm-ups, Howard stood no more than 10 feet from Hill, puffed on a cigar and glared menacingly. Hill kept his cool—he was no fool—and responded by catching a school-record 10 passes, although the Terps lost, 21-6.

** Reeves later described the talent level at Clemson as shockingly low and that his teammates could not hold a candle to the players at all-black South Carolina State.

Add Comment