It was an interesting setting and an interesting conversation. Prior to the Orange-White Game at Memorial Stadium sometime in the mid-1980s, the coaches and other staffers of the University of Texas athletic department were cooking up an eggs-and-sausage breakfast for a sizable number of football fanatics. Seems sort of quaint from the perspective of 2016, but there we were. The line moved slowly, so we had time to get to know our temporary neighbors.

He could play—then or now

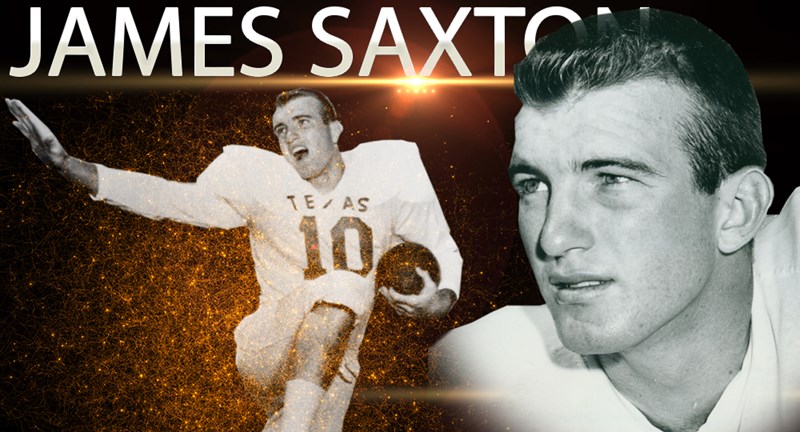

I was soon chatting with a man whose opinion I valued. It is important to point out that he was of African descent. Apparently a native of Austin, he had been  attending UT football games for longer than I had—going back to the 1950s. Whether I asked him point blank or he volunteered the information, he was emphatic that the quality of football had improved since racial integration. I followed up by asking him whether even a single guy from the Jim Crow era could play and star today. Just one, he said, James Saxton, whose varsity years for the Longhorns spanned 1959 to 1961: “Whoa, man, he could go! That Saxton could really play some ball.”

attending UT football games for longer than I had—going back to the 1950s. Whether I asked him point blank or he volunteered the information, he was emphatic that the quality of football had improved since racial integration. I followed up by asking him whether even a single guy from the Jim Crow era could play and star today. Just one, he said, James Saxton, whose varsity years for the Longhorns spanned 1959 to 1961: “Whoa, man, he could go! That Saxton could really play some ball.”

Long before I left Austin for Korea, I knew Saxton was sick. He was descending into the maw of Alzheimer’s disease. For no particular reason, a few days ago I Googled him and found that he had died in May 2014. So more than two years after the fact, I would like to offer a reminiscence of this fabulous footballer.

7.9 yards per carry

A native of Palestine in east Texas, he was planning to go to Rice before Darrell Royal showed up late in the recruiting season. Saxton opted to be a Longhorn rather than an Owl. His first two years in Austin were inauspicious as he was a running quarterback and buried on the depth chart. Even so, his ability was evident. Saxton, 5′ 11″ and 164 pounds, ran “like a bucket full of minnows” and was “as fast as small-town gossip,” to recall two of DKR’s better known lines. Before Saxton’s junior year, he was moved to tailback in Texas’ wing-T formation. The results were splendid as he was named all-Southwest Conference in 1960. Saxton’s showing the next year must be what so impressed my friend at the Orange-White Game a quarter-century later: He scored nine touchdowns and carried the ball 107 times for 846 yards—a stunning 7.9-yard average. That remains a school record. He had scoring runs of 80, 79, 66, 56, 49 and 45 yards. Only a late-season upset by TCU kept the Horns from winning the 1961 national championship; they finished third in the AP poll. Saxton was an All-American and a Heisman Trophy finalist.

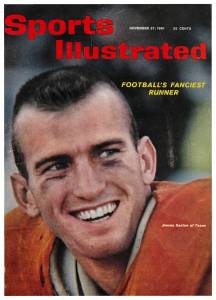

What follows is my most vivid memory of UT’s whippet-like running back. I was in the den of my family’s home in Dallas, watching a game on TV. The Horns were winning big. (Almost every game that year was a blowout.) Fairly close to the goal line, QB Mike Cotten handed the ball to Saxton. He sped around right end with breathtaking speed, scoring easily. Yes, I was enamored of the Longhorns’ No. 10, who appeared on the cover of the November 27, 1961 Sports Illustrated with the line “Football’s Fanciest Runner.”

What follows is my most vivid memory of UT’s whippet-like running back. I was in the den of my family’s home in Dallas, watching a game on TV. The Horns were winning big. (Almost every game that year was a blowout.) Fairly close to the goal line, QB Mike Cotten handed the ball to Saxton. He sped around right end with breathtaking speed, scoring easily. Yes, I was enamored of the Longhorns’ No. 10, who appeared on the cover of the November 27, 1961 Sports Illustrated with the line “Football’s Fanciest Runner.”

Let me pause and say this was the last year UT wore bright orange jerseys at home. Royal claimed to have found proof that the original color was darker and somewhat muted. At his instigation, “burnt” orange has been our lot since 1962. I think this was a mistake, as I told the coach once in an interview—tactfully, of course. I much prefer the bright orange worn by Jimmy Saxton and his peers.

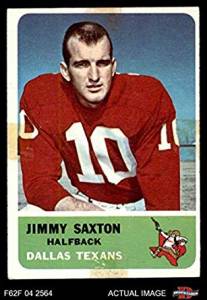

Saxton in the pros

He had a brief and uneventful professional career. A third-round pick by the Dallas Texans of the American Football League, Saxton had no chance whatsoever of moving Abner Haynes out of the backfield. He carried three times—thrice, I tell you—in the 1962  season for a single yard. He caught five passes for 64 yards. No TDs. His biggest contribution came at Jeppesen Stadium in Houston where the Oilers and Texans played for the AFL title. He punted twice in Dallas’ 20-17 double-overtime victory. Lamar Hunt moved the franchise to Kansas City not long afterward, and Saxton declined to go north. He wanted to start a business career, and truthfully he was not big enough for pro ball.

season for a single yard. He caught five passes for 64 yards. No TDs. His biggest contribution came at Jeppesen Stadium in Houston where the Oilers and Texans played for the AFL title. He punted twice in Dallas’ 20-17 double-overtime victory. Lamar Hunt moved the franchise to Kansas City not long afterward, and Saxton declined to go north. He wanted to start a business career, and truthfully he was not big enough for pro ball.

Saxton became a prominent banker, and spent time as the head of the Austin Chamber of Commerce and the State Board of Insurance. His gridiron greatness was not forgotten, as he won induction into the UT Hall of Honor, the Texas Sports Hall of Fame and the College Football Hall of Fame.

Add Comment