The 1956 football season was a terrible one in University of Texas annals. The Longhorns were en route to a 1-9 record, their only victory coming by one point against lowly Tulane. Southern California had beaten UT 44-20 in the season opener, and things were even worse against arch-rival Oklahoma: 45-0. Two days after that demoralizing loss to the Sooners, coach Ed Price was in his office at Gregory Gym when he got a surprise visitor. Marion George Ford, Jr. introduced himself to the coach. One of a handful of black undergraduates at UT, he had come to offer his services.

Ford told Price a bit about his background—that he had been an all-state lineman at Wheatley High School in Houston, that he had spent two years at the University of Illinois before transferring to UT and that he was in shape. Ford had not gone to Dallas to see the Longhorns get whipped by OU, but he listened to the game on the radio.

“Ed,” the brash Ford said, “you need me. I can help you.” Price, a three-sport star at UT in the early 1930s, had been the head football coach since 1951 but everything was going downhill. He did not require anybody, much less a student, telling him the obvious. Price probably knew he would be fired at the end of the season, but he gave no consideration whatsoever to Marion Ford’s proposal. “I just can’t do it, son. My hands are tied,” were Price’s words of woe.

Whether Ford restated his willingness to don the orange and white, I am not sure. Probably not, however. Ford apprised me of this encounter nearly 30 years later when I was interviewing him for my book, Breaking the Ice / Racial Integration of Southwest Conference Football. Begging and supplicating were not his style, but he may have told the coach some version of what he told me: “I could have handled the pressure. I thrive on that stuff.”

It was not going to happen, but what if Price had thrown caution to the wind and put Ford on his team? Suit him up, let him play. I tell you, a powder keg would have exploded in Austin, Houston, Dallas, Fort Worth, College Station, Waco and Fayetteville. All the schools of the SWC adhered to an unwritten but very real “gentleman’s agreement” whereby black players were off limits. Integration of the league’s teams was something most swore would never happen, or maybe it would—but far in the future. If Ford had taken the field with the other Longhorns the next game, against Arkansas at Memorial Stadium on October 20, 1956, there would have been an uproar. Ford, whether he was a starter or a sub, would have been subjected to some hard licks by the visiting Razorbacks. Maybe a few of his teammates would not have been too friendly. As he told me, he could have dealt with all that and more. Ford might have been a rock in the line, enabling the Horns to score a few more TD’s and hold the opponents down somewhat (guys went both ways back then). The one-point loss to SMU and the three-point loss to Baylor might have been victories. Regardless of that, what a victory the University of Texas would have had by simply adding him to the roster. Instead, as we know, UT was among the last of the big southern schools to integrate.

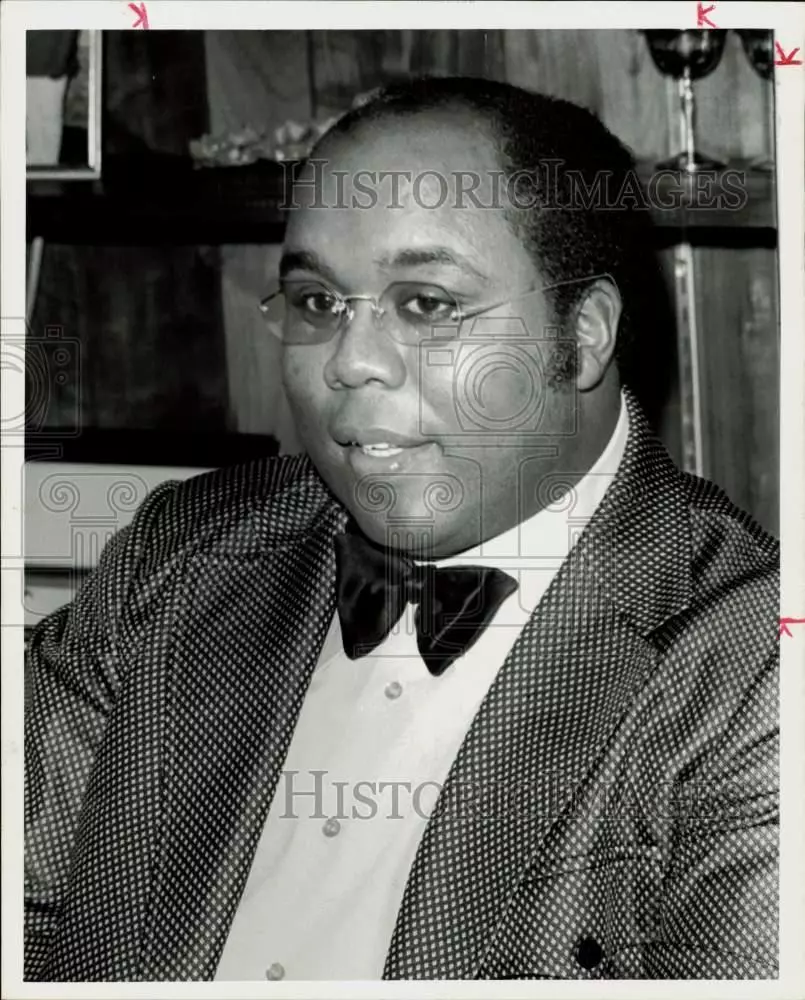

After Price demurred, Ford swore off athletica and went straight academe. He earned a degree in chemical engineering and soon became the first black student to graduate from UT Dental Branch at Houston. Dr. Ford won several fellowships and later did post-graduate work at the University of Bonn. He became fluent in German and French, and established dental clinics in Ghana, Indonesia and Tanzania. Upon returning to the USA, he had a prosperous practice of his own. A wheeler-dealer with a gregarious personality and a wry sense of humor, he became wealthy enough to purchase a series of classic automobiles. When Houston was about to bust into riots after the assassination of Martin Luther King in April 1968, Dr. Ford went out into the streets and mediated racial tensions. He was also well known for his dancing skills.

After his death in 2001, the Texas House of Representatives passed a resolution paying tribute to the life of this unique man.

3 Comments

My father was truly a unique man. Thank you for writing this. Namaste

Mario Robicheaux, you are the son of Dr. Ford?

Yessir I am privileged to say

Add Comment