Almost as soon as former University of Texas football coach Darrell Royal breathed his last on November 7, 2012, there began the encomiums, the flowery tributes, the hosannas in the highest. It seemed that sports writers, fans and ex-players were in a mad rush to see who could best praise him. Perhaps the most egregious was Dan Jenkins who said DKR was “right up there with the Alamo.” This is not journalism, it’s hagiography. Saint Darrell realized he was not perfect. Known for his folksy sayings, he once admitted, “I’ve sure as s— got some chinks in my armor.”

Before going any further, I will get in line with the kind words for the long-retired coach. I liked and admired Royal. I interviewed him several times and met him informally as well. His UT teams won 167 games during his 20 years in Austin, 11 Southwest Conference championships and 3 national championships—1963, 1969 and 1970—the latter of which was shared with Nebraska. Royal was a heck of a coach in his time, and in no way will I denigrate his achievements; I have no axe to grind or vendetta against the man. Nevertheless, I have a somewhat more objective view of Royal than Jenkins and other such individuals.

He played as a quarterback, punter and defensive back at Oklahoma in the late 1940s, and immediately got into coaching. “Impatience” is the word that best defined him until he arrived in Austin. He was an assistant for one year each at North Carolina State, Tulsa and Mississippi State before somehow being hired as head coach of the Edmonton Eskimos of the Canadian Football League. His team went 12-4, but Royal had no interest in staying up north. He returned to Starkville where he coached MSU in the 1954 and 1955 seasons. Both times, the Bulldogs went 6-4. Then he was off to the University of Washington, leading the Huskies to a 5-5 record in one season. At UW, as in Edmonton, there were a few black players on his team. That is significant in light of what happened—or more precisely, what did not happen—in later years.

After seven peripatetic seasons, he was hired at UT. Royal was not the first choice, but he got strong recommendations. He took over a program in awful shape. The Longhorns had gone 1-9 in 1956, but he instilled a new culture. Greater demands were put on the players, and they responded. Texas had a 6-3-1 regular season record in 1957 but got bludgeoned by Mississippi in the Sugar Bowl. The orange and white were off and running. Up through 1964, they had seasons that were never less than superb—capped by the 1963 national crown, for which Royal was named coach of the year. Things certainly had changed on the 40 Acres.

Then, for reasons that still seem perplexing, mediocrity returned. The team lost four games in 1965, 1966 and 1967, as Arkansas, SMU and Texas A&M represented the SWC in the Cotton Bowl. Had Royal lost his mojo? Had he gotten lazy? Then, just as suddenly, he righted the ship. Employing the high-powered Wishbone offense, UT went 30-2-1 from 1968 to 1970 and won a pair of national championships. His remaining seasons—when I was a wet-behind-the-ears student in Austin—were mostly good. The 1972 Horns were 10-1 and finished No. 3 in the final AP poll. After a strenuous 5-5-1 mark in 1976, he’d had enough. He retired from coaching at age 52.

Royal had been the athletic director at Texas since 1962 and remained in that role through 1980, but it was a caretaker position for him. That was not unusual at the time, when college athletic budgets had not yet grown to the outsize proportions we see today. The AD job supplemented his paycheck. When he retired from that, he was given a sinecure wherein he was called an advisor to the president of the university. Royal had an office on campus and a secretary, and was occasionally asked to do something. For the most part, though, he was a glad-hander and a guy who played golf as often as he liked. I realize he later got Alzheimer’s disease, but it appears that he coasted the final 36 years of his life.

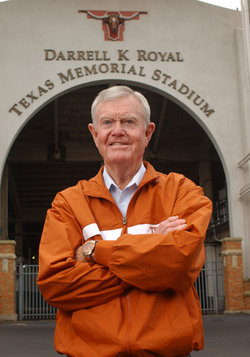

In 1996, as part of a huge fundraising campaign for the UT athletic department, his name was appended to Memorial Stadium. I did not favor this for two reasons: (1) The stadium was built in 1924 to honor Texans who had fought in World War I. That was later changed to include vets from World War II, Korea and Vietnam. And (2) he sat on his hands during the crucial integration years. Royal, so often recalled as a powerful man, a leader and one who knew right from wrong, blew it big time on this issue.

I will summarize. The UT administration officially opened athletics to persons of all races in November 1963. Royal could have taken immediate action, but he did not. (In point of fact, he could have forced the issue before the Board of Regents gave its OK. Even in the late 1950s, he was in such a strong position that he could have said, “This is how it’s going to be. Follow me.”) Now, let’s not deny the difficulty of bringing in black players along with European-American ones. Segregation had been around for a long time, and retrograde attitudes had to be confronted. Problems arose whenever a college football program integrated, but they were overcome with wise leadership. The world did not stop spinning, as some people feared. Royal could have deftly handled arch-conservatives in the UT administration, and among alumni and fans. He was the man with the power to bring about these changes. Nobody ever called DKR a social visionary, but he was practical and wanted to win ball games. In the mid-1960s, superb black players from Texas such as Warren McVea, Bubba Smith, Gene Washington, Mel Farr and Jerry LeVias were there for the taking. When informed that Smith hoped to be a Longhorn, Royal said if he wanted to come to Austin and try out he was welcome to do so. Smith declined, went to Michigan State, was a two-time All-American and the first overall pick in the 1967 NFL draft. Such guys are not generally asked to try out.

When I ponder this, I think of the teams Royal could have fielded. Instead of that mysterious three-year swoon the Horns had, they could have been on top of the college football world and pointing the way for other southern universities—let’s open it up to all athletes, not just to those of European descent. Instead, Royal sat and waited. He let men like Hayden Fry at SMU do the hard work, taking the slings and arrows of racists although he benefited in the late 1960s from LeVias and other black athletes. As the seasons went by, Royal continued to dither and make excuses. He was looking for a good boy who went to church every Sunday, made straight A’s and flossed regularly. Royal often used the “lousy education” angle. In truth, a lot of black Texans were quite well educated in their Jim Crow-mandated schools. If they could succeed academically at Washington, Missouri, Michigan State, UCLA, SMU, Houston and elsewhere, they could do just fine at UT. Royal’s specious reasoning only fueled his reputation as someone who was content to keep things as they were. Even now, many blacks and liberal-minded European-Americans hold an unshakeable negative opinion of him.

In 2005 when Texas was on its way to another national title and Vince Young was being hailed as one of the top quarterbacks in college football history, Royal was interviewed by the New York Times. Some 35 years after he belatedly integrated the Longhorns program, Royal was willing to concede: “A lot of us should have acted earlier.”

Royal’s name may be fairly listed alongside those of Bear Bryant (Alabama), Charlie McClendon (LSU), Frank Howard (Clemson), Ralph “Shug” Jordan (Auburn), Frank Broyles (Arkansas) and Johnny Vaught (Mississippi) as old-time southern coaches who waited until the bitter end to integrate. I see no reason in cutting them any more slack than necessary. As DKR stated, they should have acted earlier, but they did not. Each of them lacked the vision, the scruples, the determination to take on this admittedly tough task. How different Royal’s legacy could have been.

It brings me back to the curious refusal of sports writers and editors who, after Royal’s death, refused to take an open-eyed look at the entirety of his career. To speak frankly does not equate to unfair criticism. Had he been a bold and courageous leader in the 1960s, people would have really sung his praises in 2012.

3 Comments

There is a flip side. As you point out in your book, “Breaking the Ice”, Texas integrated track before LeVias enrolled at SMU. Royal was AD. This integration happened with his approval. He could have resisted. He didn’t.

Royal integrated UT athletics in 1963, seven years after the university. That compares very favorably to other schools integrating.

I never understood why the first AD to integrate in Texas gets panned, while guys like Switzer (who never integrated anything) gets applauded, except- Switzer tooted his horn and ran down Royal in recruiting.

Oh please. UT technically integrated all athletics in 1963 (did I not mention this?), and so what if the track team let a black guy run? It was a relatively inconsequential change, and I see no reason to give Royal “credit.” Football mattered, and he sat on his hands. I stand by everything I said in this article.

Add Comment