While having coffee with colleagues after lunch recently, one of them expressed puzzlement as to why I would be reading the biography of a man, Samuel Johnson, who lived more than 250 years ago. In point of fact, I have read books going back much farther than Johnson’s birth in 1709 in Lichfield, England. Since he is regarded as one of the preeminent men of letters in English history, that is reason enough to look into his life. Now, having finished Jeffrey Meyers’ Samuel Johnson / The Struggle (published in 2008) and done other research, I will rather presumptuously attempt to characterize him. Please note that I am no scholar. Johnson has been dissected and written about by many people whose credentials far exceed my own; I recently learned of a man at Yale University who devoted more than 50 years of his life to Johnsonian studies.

and done other research, I will rather presumptuously attempt to characterize him. Please note that I am no scholar. Johnson has been dissected and written about by many people whose credentials far exceed my own; I recently learned of a man at Yale University who devoted more than 50 years of his life to Johnsonian studies.

Ugly on the outside

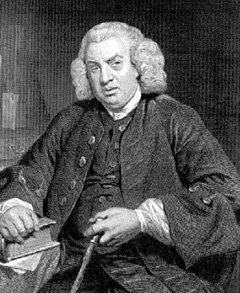

So back to Johnson’s birth. His mother had a healthy baby but turned him over to a wet nurse. She fed him bad milk which resulted in him losing sight in his left eye and hearing in his left ear. That was not all; the boy also developed scrofula, a disfiguring skin problem, and Tourette syndrome which caused him to have facial tics and other spasmodic movements that lasted throughout his life. To make matters worse, he dressed and ate in a slovenly manner. Viewed from the outside, Johnson was an ugly and even repellent person. But he had a couple of advantages: he was blessed with an absolutely brilliant mind, and his father was a bookseller. Young Sam read widely and could absorb information with ease, then make cogent comments thereon. He enrolled at the University of Oxford but dropped out after just one year when financial constraints became too much. Unable to make a living as a teacher due to his ungainly appearance, Johnson decided to pursue the invisible occupation of authorship. And where better to do that than in London?

On March 2, 1737, he and a former pupil, David Garrick, left Lichfield for the English capital. Virtually penniless, they took turns riding a horse on the 104-mile journey. I think this is very interesting since the two young men had such bright futures. Garrick would become the greatest actor of his day as well as a playwright, theater manager and producer. He helped solidify the reputation of Shakespeare among theater-goers. Garrick won fame and fortune much earlier than did Johnson, and thus there was a bit of an edge to their relationship.

Paying his dues

Johnson toiled for years as a “Grub Street hack,” writing anything for anybody who would pay. He wrote periodicals called The Rambler, The Idler and The Adventurer in which he expounded on a vast array of topics in neo-classical style. There followed biographies, literary criticism, a novel, a play, sermons, poetry and even some law lectures for a friend who was too lazy to write them himself. Johnson really came to prominence with his Dictionary of the English Language (1755). While it had taken him nine years, he created the first comprehensive and authoritative English dictionary. It was a monumental achievement whose value can hardly be overstated. Johnson followed that with The Plays of William Shakespeare (1765) in which he edited and clarified all of the Bard’s dramatic works. The Lives of the Poets (1781) was, in the view of many, Johnson’s finest writing.

Johnson toiled for years as a “Grub Street hack,” writing anything for anybody who would pay. He wrote periodicals called The Rambler, The Idler and The Adventurer in which he expounded on a vast array of topics in neo-classical style. There followed biographies, literary criticism, a novel, a play, sermons, poetry and even some law lectures for a friend who was too lazy to write them himself. Johnson really came to prominence with his Dictionary of the English Language (1755). While it had taken him nine years, he created the first comprehensive and authoritative English dictionary. It was a monumental achievement whose value can hardly be overstated. Johnson followed that with The Plays of William Shakespeare (1765) in which he edited and clarified all of the Bard’s dramatic works. The Lives of the Poets (1781) was, in the view of many, Johnson’s finest writing.

He was a literary colossus and a sage who dispensed wit and wisdom in varying doses. A towering figure often compared to a lion or a bear, Johnson was the most prominent man in England by the time he turned 50. He was awarded honorary degrees from Oxford and Trinity College, Dublin. While he might be called politically conservative, he was progressive on several key issues. He opposed slavery, capital punishment, colonialism and unnecessary wars. He was genuinely concerned about the wretched poverty he saw in the streets and hovels of London, and gave his own money to help alleviate it. Johnson was also an emotional man who laughed and wept copiously; he fought depression and, although a card-carrying member of the Church of England, feared eternal damnation.

In reading Meyers’ book, I was more than a little surprised to learn that Johnson engaged in flagellation and sado-masochism. A wealthy woman he knew, Hester Thrale, adored him and let him live at her  mansion known as Streatham for nearly 20 years. He asked Mrs. Thrale to bind and whip him with regularity. Although reluctant and abhored by the practice, she complied.

mansion known as Streatham for nearly 20 years. He asked Mrs. Thrale to bind and whip him with regularity. Although reluctant and abhored by the practice, she complied.

Boswell’s masterpiece

I cannot finish this piece without mentioning The Life of Johnson (1791) by James Boswell. It has been called the greatest biography ever written because of the way the Scottish author portrayed him—acknowledging Johnson’s imperfections while showing him as a man in full, an eloquent writer and witty raconteur like no other. Even now, academics debate whether Johnson would have faded into relative obscurity if not for Boswell’s magnum opus

Add Comment