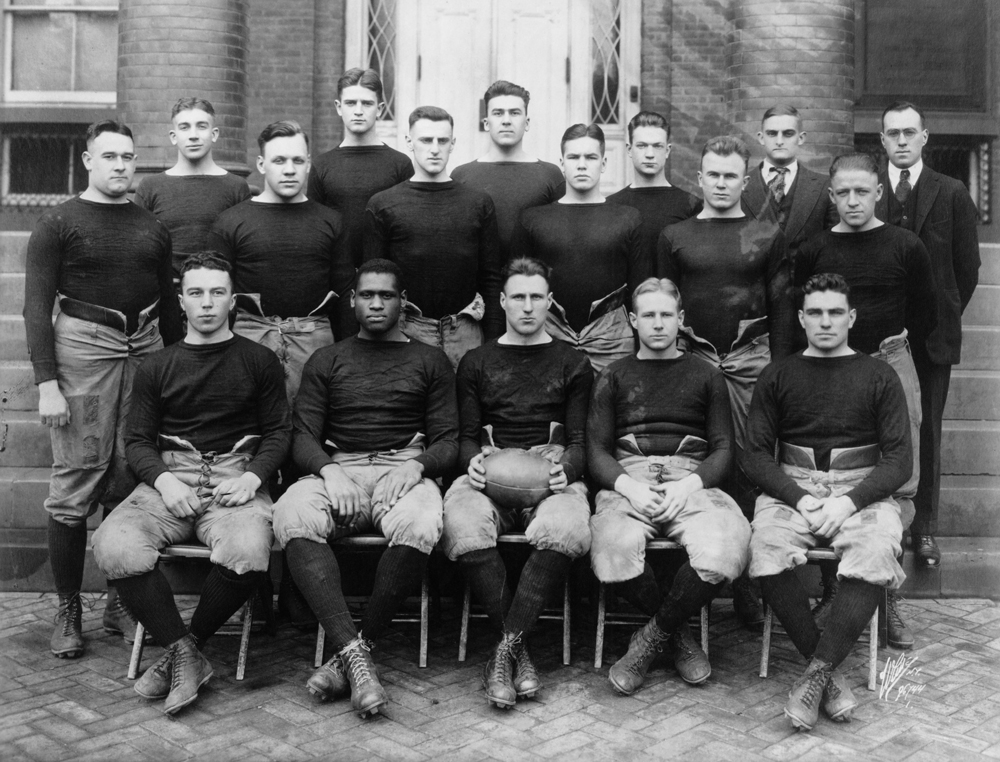

College football got its start in 1869 when Princeton and Rutgers faced off in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Soon adopting the sport were Harvard, Yale, Cornell, Michigan and many others. And while the identity of the first black player at erstwhile European-American schools is uncertain, the honor seems to go to teammates William Jackson and William Lewis of Amherst 20 years later. Some of the other early black stars would include George Jewett of Michigan, George Flippin of Nebraska, Matthew Bullock of Dartmouth, Fritz Pollard of Brown (the first black man to play in the Rose Bowl and possibly the first in pro football), Paul Robeson of Rutgers (Robeson, of course, later went on to fame as a singer, orator and civil rights activist), Duke Slater of Iowa, Joe Lillard of Oregon, Bobby Marshall of Minnesota, Wilmeth Sidat-Singh of Syracuse, Brice Taylor of Southern California, Jerome “Brud” Holland of Cornell, Marion Motley of Nevada and Levi Jackson of Yale.

Trice and Bright

None of them had it easy. Virtually all could tell horror stories about discrimination and abuse. I will give two particularly egregious examples. Jack Trice integrated the Iowa State football team in 1923. In just his second varsity game, against Minnesota, he suffered a broken collar bone when several Gophers gang-tackled him at the end of a play. Trice left the field on a stretcher and soon died of internal  bleeding and a ruptured lung. Six decades later, Iowa State honored Trice by naming its stadium after him. The second example involves Johnny Bright of Drake, who led the nation in offense in 1949 and 1950 and was doing the same in 1951 and might have been the first black player to win the Heisman Trophy if not for a racist attack on the field. A vicious blow to the face (in the days before face masks) by Wilbanks Smith of Oklahoma A&M fractured Bright’s jaw and caused him to miss two games and thus the honors he deserved. A series of photographs of Bright being assaulted on the field won the Pulitzer Prize and heightened awareness of the whole issue of athletic integration.

bleeding and a ruptured lung. Six decades later, Iowa State honored Trice by naming its stadium after him. The second example involves Johnny Bright of Drake, who led the nation in offense in 1949 and 1950 and was doing the same in 1951 and might have been the first black player to win the Heisman Trophy if not for a racist attack on the field. A vicious blow to the face (in the days before face masks) by Wilbanks Smith of Oklahoma A&M fractured Bright’s jaw and caused him to miss two games and thus the honors he deserved. A series of photographs of Bright being assaulted on the field won the Pulitzer Prize and heightened awareness of the whole issue of athletic integration.

But the deck was stacked against black athletes in those days. None were named first-team all-American between 1918 and 1937, a ridiculous oversight given the abbreviated list of fine players given above. And the National Football League had no black players from 1934 to 1946, the first of three so-called gentleman’s agreements in this story. (By the way, the last NFL team to integrate was the Washington Redskins in 1962.) The second gentleman’s agreement pertains to the interaction of Southern and non-Southern teams back in those days. After college football integration had become a reality elsewhere, the South closed up. Most teams from Texas to Maryland just played among themselves. When a Southern team went to play an opponent from the North or West, the coaches of those schools acceded to the request of the Southern coaches by sitting their black player or players. And in those rare cases when they came South, their black athletes were often left behind because they surely were not going to play and they wanted to avoid the indignity of dealing with Jim Crow arrangements. But the players, coaches and administrators of these non-Southern colleges increasingly resisted such a setup, which, naturally, favored their Southern opponents. The aforementioned Johnny Bright played for Drake, an Iowa school that chose to visit Stillwater, Oklahoma for a football game in 1951. The South, by resisting integration, became more and more isolated. LSU, for example, did not play a non-Southern opponent, whether at home or on the road, from 1942 until 1970.

Post-war changes

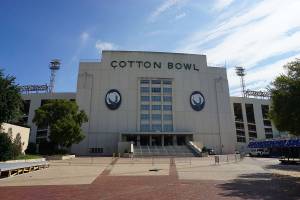

But things were evolving. It was considered a sign of social progress when, on October 11, 1947, Harvard played Virginia in Charlottesville. The Crimson’s lineman, Chester Pierce, became the first black athlete to compete in any of the former Confederate states on the home turf of a European-American college. By Pierce’s recollection, the Cavaliers (three-fifths of whom were World War II veterans and aware that blacks helped in the struggle for democracy abroad) were as civil as any football players, but many of the fans at Scott Stadium were not. UVa, for the record, won by a score of 47-0. Just two months later, Wally Triplett and Dennis Hoggard accompanied their Penn State teammates to play SMU in the Cotton Bowl. Yet we must remember the times. There were people in Texas whose attitude about athletic integration could be summed up in the words “over my dead body.” And the thought of having black players on the football teams of the Southwest Conference was just as abhorrent to most coaches, alumni and administrators of the SWC, which then consisted of Texas, Arkansas, Texas A&M, SMU, Rice, Baylor and TCU.

The Southwest Conference, which lasted from 1915 until its dissolution in 1995, a total of 81 years, was one of the premier conferences in the country. In the pre-integration era, it could boast of five national champions—SMU in 1935, TCU in 1938, Texas A&M in 1939, Texas in 1963 and Arkansas in 1964, and three Heisman Trophy winners—Davey O’Brien of TCU in 1938, Doak Walker of SMU in 1948 (widely regarded as its best player up to that time), and John David Crow of Texas A&M in 1957. There were dozens of all-Americans and future pro stars. The SWC got the lion’s share of media attention in this region, and why not? It had the premier schools, the money, the alumni and the big stadiums.

The Southwest Conference may have been royalty here, but it did not matter to many of Texas’ black citizens. Oh, a handful of black football fans attended SWC games and sat in segregated areas and had their own restrooms and water fountains inside Texas Memorial Stadium, Amon Carter Stadium, Rice Stadium, Baylor Stadium, Razorback Stadium, Kyle Field, Jones Stadium (Texas Tech joined the conference in 1960) and the Cotton Bowl. Most, however, paid scant attention, since their sons were forbidden from participating by custom and/or edict. Generations of bigotry made the idea of integration of SWC football unthinkable, although a handful of black graduate students had been allowed on some campuses by the late 1940s. To the long-suffering black citizens of Texas, change must have seemed to be coming at a glacial pace.

To be clear about one thing, there was no shortage of young men who were capable of helping SWC teams win football games. So many never got a chance to develop their athletic talents, given the social, political and economic realities of the day. Most of those who did play college football went to black schools such as Prairie View and Texas Southern or out-of-state places like Grambling, Jackson State or Florida A&M. But since the 1920s, a few had gone up north or out west and done quite well. A short list of such Texans would include Oze Simmons of Iowa, Charley Taylor of Arizona State, Junior Coffey of Washington, Johnny Roland of Missouri, Mel Farr of UCLA, and Bubba Smith and Gene Washington of Michigan State. Simmons’ career, unfortunately, fell during that time when the NFL disallowed black players, but Taylor became a star with the Washington Redskins, Coffey with the Atlanta Falcons, Roland with the St. Louis Cardinals, Farr with the Detroit Lions, Smith with the Baltimore Colts and Washington with the Minnesota Vikings. All of these guys were outstanding football players whose academic abilities ranged from fair to brilliant (as with their European-American counterparts), some earning advanced degrees. Coaches of the Southwest Conference knew there was a virtual goldmine of athletic talent going untapped, but they dared not.

In lieu of alternatives, Haynes walks on at North Texas

While the members of the wealthy, tradition-laden SWC were delaying the inevitable, others were moving forward. It was left to the “lesser” schools of the state to start recruiting black athletes. In all likelihood, the process began in the junior colleges and in other sports where little attention was paid. Evidence of that can be seen in the experience of basketball player Charley Brown. He came from the segregated schools of Atlanta in east Texas, served in the Air Force during the Korean War and then  spent a year at Amarillo Junior College before going to Texas Western (now Texas-El Paso) in 1957. That same year, Abner Haynes walked on at North Texas State. Coach Odus Mitchell had permission from the school’s administration to take Haynes who, although he quickly became the offensive and defensive star of the football team, was not allowed to live on campus. He had other painful encounters with Jim Crow while playing for the Eagles, the worst being when Ole Miss, Mississippi State and Chattanooga canceled their games with North Texas. Following close behind Haynes (by then a star with the Dallas Texans/Kansas City Chiefs) were Leford Fant of Texas Western, Sid Blanks of Texas A&I (rather significantly the captain of the team in his senior year), Kenneth Decker of McMurry and “Pistol” Pete Pedro of West Texas State. Simultaneously, Prentice Gautt became the first black varsity player at the University of Oklahoma, so it looked as though integration of college athletics in the South was moving along.

spent a year at Amarillo Junior College before going to Texas Western (now Texas-El Paso) in 1957. That same year, Abner Haynes walked on at North Texas State. Coach Odus Mitchell had permission from the school’s administration to take Haynes who, although he quickly became the offensive and defensive star of the football team, was not allowed to live on campus. He had other painful encounters with Jim Crow while playing for the Eagles, the worst being when Ole Miss, Mississippi State and Chattanooga canceled their games with North Texas. Following close behind Haynes (by then a star with the Dallas Texans/Kansas City Chiefs) were Leford Fant of Texas Western, Sid Blanks of Texas A&I (rather significantly the captain of the team in his senior year), Kenneth Decker of McMurry and “Pistol” Pete Pedro of West Texas State. Simultaneously, Prentice Gautt became the first black varsity player at the University of Oklahoma, so it looked as though integration of college athletics in the South was moving along.

Just as non-SWC colleges were integrating, so were some Texas high schools, albeit slowly. Following the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision outlawing public school segregation, school systems across the South were slow to act upon it. The first Texas cities to do so were San Antonio, Corpus Christi, Austin, El Paso, Kerrville, Harlingen and San Angelo—all with fairly small black populations—starting perhaps inevitably with a handful of carefully chosen black students crossing over to the European-American schools. And while it was an uneasy time, situations as severe as Little Rock, Arkansas circa 1957 did not occur in the Lone Star State. Team sports, palpable evidence of blacks and European-Americans working together for a common goal, were often the opening wedge to a community’s integration process. Yet injustice was common there, too. In 1956, Wharton High School chose to forfeit a championship girls basketball game because Beeville High School had a black substitute player. The same year, James Lott, a talented black running back for Refugio, scored over 100 points in the season but was left off the all-district football team. By the fall of 1964, only a quarter of Texas’ black students attended integrated schools. Many European-American Texans (though surely not all) remained adamant against even token integration, yet time was catching up with them. The civil rights movement was bearing fruit in countless ways.

So what was the Southwest Conference waiting for? Their denials notwithstanding, the coaches appear to have been bound by the third and final gentleman’s agreement. On the cusp of integration, the SWC’s coaches were Darrell Royal of Texas, Frank Broyles of Arkansas, Jess Neely of Rice, Abe Martin of TCU, J.T. King of Texas Tech, John Bridgers of Baylor, Hank Foldberg of Texas A&M and Hayden Fry of SMU. The conference was obviously dragging its heels. In 1963, with some pressure by Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson the University of Texas Board of Regents overturned a rule that had prohibited blacks from playing on its various intercollegiate teams, which resulted in James Means, Oliver Patterson and Cecil Carter joining the Longhorn track program. Basketball was just around the corner and so, it seemed, was King Football.

That brings us to Warren McVea, one of the most ballyhooed Texas athletes of the 1960s. As a running back for Brackenridge High School in San Antonio, he led the team to a state title and scored a staggering 68 touchdowns in his final two seasons. Purportedly able to run crooked faster than most players could run straight, McVea was known as “Mac the Knife.” He was smart and yet lackadaisical, passing each grade mostly by virtue of his athletic splendor. And to make matters worse, he was once charged with statutory rape, led a brief revolt against the coaching staff over disciplinary issues and developed a reputation that scared many collegiate suitors, especially those of the Southwest Conference.

McVea to UH

When McVea chose the University of Houston over Southern Cal, Nebraska, Missouri, Oklahoma and many others, it was the beginning of the end game for segregation in the SWC. A 1967 Sports Illustrated article jokingly claimed that “McVea was rumored to have received an automobile, a wardrobe to equal a South American dictator’s, free trips home to San Antonio any time he wished to go, a telephone card, a suite of rooms at the Tidelands Hotel his freshman year and a four-year salary of $40,000.” Indeed, UH was put on probation by the National Collegiate Athletic Association shortly afterward for recruiting violations.

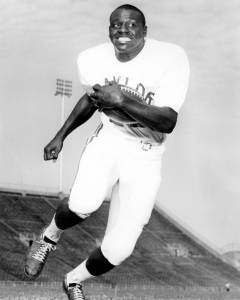

He had an uneven career, which coincided with the opening of the Houston Astrodome. Treated as a prima donna by coach Bill Yeoman, McVea had tiffs with teammates, including one well-publicized shoving match with Ken Hebert in the middle of a game. He demonstrated courage as one of the first black players to enter the stadiums at Texas A&M, Miami, Tennessee, Mississippi (both in Memphis and in Oxford), Kentucky and Mississippi State. In some of those games, Confederate flags were waved, the  bands played “Dixie” incessantly and fans hurled racial abuse and various airborne missiles at McVea and his teammates. It was not for the faint of heart. McVea’s high point was undoubtedly in 1966 on the road against Michigan State. Before 76,000 fans, he gained 155 yards on just 14 carries in a 37-7 win that lifted the Cougars to No. 3 in the nation. Although a groin injury limited his effectiveness throughout his senior year, McVea went on play for the Cincinnati Bengals and Kansas City Chiefs, with whom he won a Super Bowl title in 1970. A pair of knee injuries made his NFL tenure a short one. McVea, who later struggled with drug and legal problems, recalled his bittersweet UH days this way: “It was terrible when I look back on what I had to go through. They got more than their money’s worth, with the respectability I brought to the team and the city.”

bands played “Dixie” incessantly and fans hurled racial abuse and various airborne missiles at McVea and his teammates. It was not for the faint of heart. McVea’s high point was undoubtedly in 1966 on the road against Michigan State. Before 76,000 fans, he gained 155 yards on just 14 carries in a 37-7 win that lifted the Cougars to No. 3 in the nation. Although a groin injury limited his effectiveness throughout his senior year, McVea went on play for the Cincinnati Bengals and Kansas City Chiefs, with whom he won a Super Bowl title in 1970. A pair of knee injuries made his NFL tenure a short one. McVea, who later struggled with drug and legal problems, recalled his bittersweet UH days this way: “It was terrible when I look back on what I had to go through. They got more than their money’s worth, with the respectability I brought to the team and the city.”

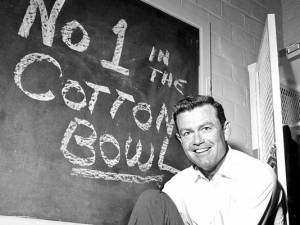

McVea had signed a scholarship with UH in 1964, and one year later the SWC (which did not admit the Cougars until 1975) changed forever. We have to begin with Hayden Fry. A native of Odessa, he had played at Baylor in the early 1950s and been an assistant there and at Arkansas before SMU hired him in 1962 for the princely sum of $13,000 per year. With the approval of SMU President Willis Tate, Fry began laying the groundwork, talking with players, assistant coaches, faculty and alumni about getting a young man who could not only help the Mustangs win football games but take the pressure of being the first black player in the storied Southwest Conference. He soon focused on Jerry LeVias, a student at Hebert High School in Beaumont. Just 5’ 9” and 170 pounds, LeVias was a halfback/receiver who ran, passed and caught, putting up big numbers for the Panthers, who made it twice to the title game of the Prairie View Interscholastic League, the black version of the University Interscholastic League, and which would be merged into the UIL in less than a decade. He was outstanding in basketball and track (capable of running 100 yards in 9.6 seconds), but football was his game. Nearly 100 schools wanted LeVias. His cousin, Mel Farr, was then a star at UCLA and urged him to come out to Los Angeles, but he was swayed by Fry, the Mustangs’ 1-9 record in 1964 notwithstanding. He signed in May 1965.

The Ponies’ No. 23

Nine years after Abner Haynes enrolled at North Texas, and with the civil rights movement ongoing, LeVias still faced considerable problems getting into and through SMU. The euphemism “cultural sensitivity” had not yet been invented, much less put to use. In his first scrimmage with the freshman team, several varsity players came over to watch, and he put on a show, making a series of spectacular catches and scoring repeatedly. But then a frustrated defender—a teammate, remember—blindsided him and caused three broken ribs.

Finally, as the 1966 season approached, it was time for the real thing. In his first varsity game, LeVias caught touchdown passes of 5 and 60 yards from quarterback Mac White and the Mustangs beat Illinois at the Cotton Bowl. He made two splendid punt returns the next week in a victory over Navy and was already being compared to the immortal Doak Walker. He almost singlehandedly won the game against Rice by throwing a 47-yard touchdown pass and catching the winning TD with nine seconds left, and his 83-yard punt return beat the Texas A&M Aggies. SMU won the Southwest Conference crown for the first time in 18 years and played Georgia in the Cotton Bowl. But I have not mentioned the conditions under which LeVias played in that tumultuous season. He was truly the Jackie Robinson of the SWC, suffering the same kinds of hateful treatment Robinson had in integrating major league baseball in 1947. Some, though not all, of his teammates and coaches were not happy to have him there, opponents regularly taunted and sought to hurt him in ways both obvious and subtle, some officials were biased against him, some fans screamed racial abuse, and there were countless mean-spirited letters and phone calls. Against TCU, in Fort Worth, there was a death threat serious enough to warrant the presence of city, state and federal law enforcement officers on the lookout for snipers.

Such mistreatment continued throughout LeVias’ career at SMU. When the Ponies played Baylor in 1967, linebacker David Anderson threw a forearm at LeVias with bad intent, resulting in profuse bleeding and an injury of his eye socket that later required surgery. Nevertheless, LeVias went back into the game and caught five more passes. After one of them, practically the entire Baylor defense drove him out of bounds and over the Bears’ telephone bench, causing a dislocated finger. Still, no penalty was called. And in his senior year, 1968, the Mustangs were back in Fort Worth to play the Horned Frogs. LeVias had caught nine passes in a game that was tied midway through the fourth quarter. Then a TCU player knocked him to the ground, uttered a racial epithet and spat in his face. LeVias took himself out of the game, threw his helmet down and announced loudly, “I quit!” Fry came over to console an angry, miserable, crying LeVias on the bench. By the time TCU was about to punt the ball, LeVias agreed to return but he also said, “Coach, I’m going to run it back for a touchdown.” Most sports fans know about Babe Ruth’s legendary called-shot home run in the 1932 World Series, the legitimacy of which has long been questioned, but this really happened. LeVias caught the punt at his 11-yard line, headed up the middle, veered right and faked out a number of defenders in front of the Frogs’ bench, crossed back to the left while dodging more would-be tacklers, cut into the open and outran everybody for an 89-yard touchdown that won the game.

Jerry LeVias’ career numbers at SMU were impressive: 155 receptions, 25 touchdowns, 3 times all-SWC and consensus all-American in 1968. At that point, he was probably the greatest player in the history of the Southwest Conference, Doak Walker included. And I don’t have to say “probably” when pondering who was the most significant because he led the way for people like Earl Campbell, Eric Dickerson, Mike Singletary and Ricky Williams. He did a lot for the black people of Texas, and the European-American  ones, too; they had all been in the Jim Crow straightjacket for a long time. LeVias, who was on the Dean’s list at SMU and an academic all-American, went on to play six years with the Houston Oilers and San Diego Chargers before starting a business career in Houston. He was inducted into the Texas Sports Hall of Fame in 1995 and the College Football Hall of Fame eight years later. LeVias knows the significance of what he did in integrating SWC football, but during a symposium at Texas A&M-Galveston in 2002, when asked if he would do it all over again, his response was a succinct “no.”

ones, too; they had all been in the Jim Crow straightjacket for a long time. LeVias, who was on the Dean’s list at SMU and an academic all-American, went on to play six years with the Houston Oilers and San Diego Chargers before starting a business career in Houston. He was inducted into the Texas Sports Hall of Fame in 1995 and the College Football Hall of Fame eight years later. LeVias knows the significance of what he did in integrating SWC football, but during a symposium at Texas A&M-Galveston in 2002, when asked if he would do it all over again, his response was a succinct “no.”

The forgotten Westbrook

Having said all that, I will now add that LeVias was technically not the first black player in SWC history. Let’s return to the summer of 1964, nearly a year before LeVias signed a scholarship offer with SMU. John Westbrook, then entering his senior year at Washington High School in Elgin, stepped into the offices of the coaching staff at Baylor University and told them of his plans to enroll there and perhaps play football. Westbrook, the son of a Baptist minister, had been ordained at age 15, and Baylor was a Baptist school, so why not? Well, for one thing, the BU Board of Trustees had only integrated the university in November 1963, and no word had been said about athletics. Like most European-American Texans back then, they did not want to think about a black guy wearing the green and gold of the Baylor Bears.

Coach John Bridgers and Chancellor Abner McCall may not have been eager, but they decided to let Westbrook walk on as a freshman in 1965. He was one of just seven black students on a campus of 7,000, the large majority of whom were sons and daughters of the South. Hostility and isolation were the norm, although to be fair to those people, they were feeling their way in an integrated world, too. Westbrook’s arrival on the Baylor football team was utterly unheralded. His time in the 40-yard dash made him one of the fastest players on the team, but he hardly got on the field that season. Freshman coaches Milburn “Catfish” Smith and Ramsey Muniz did all they could to discourage Westbrook with verbal taunts and brutal three-on-one drills. He was ignored by most of his teammates and goaded by a few others.

And to make matters worse, some of the black people in Waco regarded him as an Uncle Tom for even making the attempt to integrate Bears football. His lonely fight, however, was made easier by the support and reassurance of Eucolia Erby, a small black man who had known Westbrook’s father. Erby came to practices, watched and encouraged him, and told him repeatedly, “Don’t quit.” His coach, Bridgers, made the decision, at the end of spring training, to award him a scholarship. That alone permitted Westbrook to stay at Baylor.

On September 10, 1966 (one week before SMU’s opener in which Jerry LeVias began his fabulous career), Baylor hosted Syracuse. The Bears were ahead by 22 points midway through the fourth quarter when Bridgers sent Westbrook into the game, making history. His three years at Baylor were not too productive, as he scored just two touchdowns and gained no more than 250 yards and suffered a serious knee injury. Two concussions were meted out, he believed, by his own teammates and coaches on the practice field. Just as LeVias was the subject of unimaginable abuse, so was Westbrook, but it was not as intense because he was not nearly the star LeVias was. Nevertheless, he suffered mightily. Westbrook once drove his ancient Studebaker to Lake Waco and contemplated rolling it into the water, ending his pain. On another occasion, he swallowed a fistful of aspirin.

He graduated from Baylor with an English degree in 1969 and declined offers to try out for the Cincinnati Bengals and Atlanta Falcons. Westbrook earned a master’s degree from Southwest Missouri State, served as pastor at churches in Tyler and Houston, and spoke at several Billy Graham crusades. In 1978, he ran a shoestring campaign for lieutenant governor and got 23 percent of the vote in the Democratic primary. Westbrook died on December 17, 1983 of a blood clot in one of his lungs. His funeral drew an overflow crowd and a list of eulogizers that included Governor Mark White and Houston Mayor Kathy Whitmire.

One of his teammates on the BU football team, Jackie Allen, recalled him thus: “No one will ever know what all John went through. He took on the role of a pioneer and should have known that they go into uncharted waters and that difficulties will be encountered, and that is just what happened.”

Westbrook described his four years at Baylor as the most miserable time of his life. “I got such a bad taste of college athletics,” he said in a 1972 oral history project with Drs. Thomas Carlton and Rufus B. Spain. “But because of football, I got an education. I learned how to live. I don’t hate football. Football isn’t dirty. It’s some of the people in football who make it dirty. I could talk for two more hours and get bitter. I’ve been able to forget a lot of the bad, and it’s not fun to recall.”

Having covered Warren McVea of Houston, Jerry LeVias of SMU and John Westbrook of Baylor, I will now summarize the first black players at the other SWC schools. First, however, I should add that having just one or two on a team was not truly integration so much as tokenism. Still, the athletic directors and coaches had to start somewhere, and I don’t mean to downplay the conflicts inherent to the integration process. There were always problems, always conflicts, always issues that had to be worked out over the years. It did not matter whether it was a big state school or a small church school, integrating the football team was not easy.

The Aggies, et al.

Texas A&M, which only admitted its first black students in 1963, had a black varsity player four years later. Receiver Sammy Williams, a walk-on from Houston, made the team but evidently did not play in the Aggies’ championship run in 1967. The next season, Hugh McElroy, another walk-on receiver, was best known for catching a game-winning touchdown pass against LSU in 1970. A&M did not have a varsity black recruit until 1971, and his name was Jerry Honore. Emory Bellard deserves credit for being the first SWC coach to start recruiting black players in large numbers in the mid-1970s.

Next up is TCU. The Horned Frogs had recruited James Cash to play basketball shortly after SMU signed LeVias. Cash was an outstanding hoopster from 1967 to 1969 (followed by an equally successful academic career culminating with a spot on the Harvard faculty), but it only happened after a serious power struggle in the highest reaches of the TCU administration. The school’s first black football player was Linzy Cole, a junior college recruit who caught 53 passes, scored 12 touchdowns and averaged 20 yards on punt returns and 25 on kickoff returns. Cole later played for the Chicago Bears, Houston Oilers and Buffalo Bills. The 1971 TCU team was full of racial dissension; black players like Raymond Rhodes, Larry Dibbles and Danny Colbert were not pleased with dreary social lives nor with the authoritarian ways of the coaching staff. Some quit or transferred, while others stayed in Fort Worth but without enthusiasm.

Danny Hardaway, quite a high school star in Lawton, Oklahoma, had no shortage of scholarship offers, so some people were surprised when he chose Texas Tech. Besides playing on the Red Raiders’ freshman football team in 1967, he scored 14 points per game for the frosh basketball team. He was 6’ 3”, weighed 206 pounds and ran the 40 in 4.7 seconds, and some fans expected Hardaway to replicate Donny Anderson, the recently departed two-time all-American. It was not to be, however. Hardaway led Texas Tech in rushing in 1969 but lost his job in 1970 and played mostly as a kick returner. He developed academic troubles and soon left school.

No other Southwest Conference institution had such difficulties integrating as Rice since its founder, William Marsh Rice, had specifically limited the student body to “white males from Harris County.” While women and non-Harris County residents were gradually admitted, the racial clause remained in force until 1965 when the Rice administration went to court to have it overturned. Three years later, the Owls signed three black players: defensive back Mike Tyler, linebacker Rodrigo Barnes and  quarterback/running back Stahle Vincent. Tyler and Barnes were assertive and independent, while Vincent was the opposite, a guy who practiced hard, played hard and never complained. Coach Bo Hagan had the courage to start him at quarterback in 1969, a decade before some other schools would consider such a thing. By 1971, Vincent had been moved to running back, where he gained 945 yards and was named all-conference. He played briefly for the Pittsburgh Steelers.

quarterback/running back Stahle Vincent. Tyler and Barnes were assertive and independent, while Vincent was the opposite, a guy who practiced hard, played hard and never complained. Coach Bo Hagan had the courage to start him at quarterback in 1969, a decade before some other schools would consider such a thing. By 1971, Vincent had been moved to running back, where he gained 945 yards and was named all-conference. He played briefly for the Pittsburgh Steelers.

The last two SWC schools were, in terms of football, the most significant—the University of Arkansas and the University of Texas. I will start with the Razorbacks. Darrell Brown was a freshman walk-on running back at Arkansas in 1965, the same year Jerry LeVias was starting out at SMU and John Westbrook at Baylor. Brown’s story is fairly dramatic. On the practice field and in the few games in which he played, his offensive teammates sometimes refused to block for him and even engaged in racist group chants. Thus he never made it to the varsity. But he might have if head coach and athletic director Frank Broyles had made it clear to everyone that Brown was to be treated fairly. One assistant coach, in particular, took it upon himself to harass and discourage Brown as much as possible. Brown had the last laugh, though, graduating on time from UA and then its law school before becoming a prominent attorney in Little Rock.

As a result, Arkansas delayed integration for five more years. That was with Jon Richardson, a fast and flashy runner who played from 1970 to 1972. In his first game, on national television against Stanford, Richardson caught a 37-yard TD pass, the first of 11 scores his sophomore year. A broken leg in 1971 slowed his progress and made him primarily a kick returner the rest of his career. Richardson, like so many others before him, felt pressure from all sides—European-Americans who hated and feared what he represented, and his own people who called him an Uncle Tom. Richardson died of a heart attack in January 2002.

Orange and white

And that brings us to the University of Texas. There is plenty to admire about UT and plenty to criticize. Texas’ flagship institution before A&M rose to that level, the wealthiest, the biggest, the one with the most alumni, the one just a mile from the state capital, could have and should have been the first to integrate its football program, and the others undoubtedly would have followed suit. Marion Ford, who had been a star at Wheatley High School in Houston, was among UT’s first black undergraduates. In the 1956 season, the Longhorns were horrible, en route to a 1-9 record. So Ford went to coach Ed Price and volunteered to come out for the team. “I was a cocky son of a bitch in those days,” Ford recollected. “I  said, ‘Ed, I could help your team. You need me.’ And he said, ‘Listen, son, it’s out of my hands. The policy is just too strong.’” Ford went on to roll up an impressive list of academic honors, graduating magna cum laude in chemical engineering, with two advanced degrees and a Fulbright scholarship. If nothing else, Marion Ford obliterated the SWC coaches’ lame excuse that they could not find academically qualified black players. Ford’s encounter with Ed Price was in 1956, ten years before Jerry LeVias and John Westbrook integrated the SMU and Baylor football teams, respectively. What a difference it would have made if Price had taken a stand and let Ford be the first black Longhorn.

said, ‘Ed, I could help your team. You need me.’ And he said, ‘Listen, son, it’s out of my hands. The policy is just too strong.’” Ford went on to roll up an impressive list of academic honors, graduating magna cum laude in chemical engineering, with two advanced degrees and a Fulbright scholarship. If nothing else, Marion Ford obliterated the SWC coaches’ lame excuse that they could not find academically qualified black players. Ford’s encounter with Ed Price was in 1956, ten years before Jerry LeVias and John Westbrook integrated the SMU and Baylor football teams, respectively. What a difference it would have made if Price had taken a stand and let Ford be the first black Longhorn.

Price got fired after that awful season and was replaced by a more familiar name, Darrell Royal. Royal, of course, would be the dominant figure in Texas football for the next two decades, during which the Horns won 164 games and three national championships. While Royal is alleged to have made racist statements in the late 1950s and early 1960s, they were never substantiated. Furthermore, many things in his private life indicate a self-made man who went out of his way to befriend and help black people. But he did not integrate when he had the chance. Royal’s 1963 team won the national title, he was voted national coach of the year, he had been given a professorship with tenure by the UT administration (an unheard-of move at the time), and Oklahoma, his alma mater, wanted him to come home. In other words, Royal was in a very strong position. But he dithered and waited, and found reasons and excuses. He sat on his hands and let others, such as Hayden Fry and John Bridgers, do the hard work of integrating SWC football. He claims to have tried to recruit Bubba Smith, Warren McVea and Jerry LeVias, but I am doubtful. During those crucial years when his supposedly racist image was being made, Royal failed to act, and that remains the biggest mistake of his coaching career.

DKR’s admission, long after the fact

In retrospect, Royal admitted, “If you’re saying we should have done it sooner, I agree with you. All of us should have, not just the University of Texas. When LeVias hit in 1966, that was when people began to change their attitudes, and let me say a lot of us needed some attitude changes…. Some people did question the old ways, and that’s the reason we had the change. Now, today, I can look back and wonder why I didn’t question it.”

In 1967, two black walk-ons were members of the UT freshman team: E.A. Curry and Robinson Parsons, but neither got to the varsity. The wise, if cynical, thing for Royal would have been to ensure that one or both of those young men made it to the Longhorn varsity, getting on the field, drawing the requisite media attention and ending the days of all-white football at Memorial Stadium. By procrastinating, Royal had painted himself into a corner. War was raging in Vietnam, there were riots in dozens of American cities, students were smoking dope and protesting everything imaginable, and DKR’s teams had yet to integrate. The 1969 Longhorns went undefeated, with memorable wins over Arkansas and Notre Dame, and are remembered today as the last national championship team without a black player.

As I mentioned earlier, UT track had been integrated since 1963 and basketball since 1969, and it happened in football in 1970 when Julius Whittier joined the varsity. He was a short but explosive offensive lineman who started for the orange and white his junior and senior seasons and later got a law degree. Whittier was followed by a trickle of black athletes like Donald Ealey, Howard Shaw and  Roosevelt Leaks. Leaks, a running back, was Texas’ first black star. He had gained over 2,500 yards in 1972 and 1973, and was favored to win the Heisman Trophy in 1974, but he suffered a knee injury in spring training which some observers thought was intentionally inflicted by a teammate. Nevertheless, he had a solid 10-year pro career with the Baltimore Colts and Buffalo Bills.

Roosevelt Leaks. Leaks, a running back, was Texas’ first black star. He had gained over 2,500 yards in 1972 and 1973, and was favored to win the Heisman Trophy in 1974, but he suffered a knee injury in spring training which some observers thought was intentionally inflicted by a teammate. Nevertheless, he had a solid 10-year pro career with the Baltimore Colts and Buffalo Bills.

The Deep South

A comparison between the SWC and the other two major Southern conferences, the Atlantic Coast Conference and the Southeastern Conference, might be instructive. What is really notable is that both integrated in the northernmost states and worked their way south. In the ACC, Darrell Hill transferred from the U.S. Naval Academy to Maryland in 1963 and did well as a receiver for the Terrapins, despite a few jeers, catcalls and and cheap shots from opponents. Robert Grant and Butch Henry played for Wake Forest from 1965 to 1967 as progress moved inexorably south to Clemson and South Carolina in 1971.

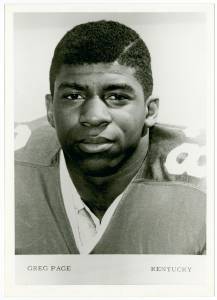

In the Southeastern Conference, it went like this: Two black players (linebacker Greg Page and defensive back Nat Northington) signed with Kentucky in 1966, but misfortune befell them both. They played on the freshman football team, but on the third day of varsity practice in the spring of 1967, Page suffered a spinal injury that left him paralyzed and in a coma for 40 days before he died. Racially motivated malfeasance from one’s teammates was not unheard of, as we have seen. But a thorough investigation  determined that Page’s death had just been an unfortunate football accident. That left Northington, who played a couple of games for the Wildcats before suffering a shoulder injury and quitting the team. Moving one state south, receiver Lester McClain was playing varsity football at Tennessee in 1968 and catching passes from a black quarterback, Condredge Holloway, by his senior year.

determined that Page’s death had just been an unfortunate football accident. That left Northington, who played a couple of games for the Wildcats before suffering a shoulder injury and quitting the team. Moving one state south, receiver Lester McClain was playing varsity football at Tennessee in 1968 and catching passes from a black quarterback, Condredge Holloway, by his senior year.

You show ’em, Bear

No school’s integration process was more analyzed or agonized than Alabama, whose coach, Paul “Bear” Bryant, was alleged (like Darrell Royal) to have made defiant statements a la George Wallace in the schoolhouse door in 1963. True or not, one game is said to have changed the Bear’s views once and for all, and that was at Legion Field in Birmingham on the night of September 12, 1970. Alabama, on the way to a desultory 6-5 record, still did not have a single black player on its varsity roster. But Southern Cal did. The Trojans were loaded with studs like Sam “Bam” Cunningham, Jimmy Jones, Clarence Davis, Al Cowlings (better known today for having driven the white Bronco in O.J. Simpson’s infamous slow chase on a Los Angeles freeway) and Charley Weaver. They whupped Bryant’s boys 42-21. It was a landmark game, even to the most bigoted observers. Bryant had two black players on his team the next year and, coincidence or not, the Crimson Tide went 11-1. The dubious honor of being the last SEC schools to integrate goes to LSU and Georgia, which waited until 1972.

Integrating college football in Texas and throughout the South was not an easy thing, and those who were in the midst of it—the heroes and even some of the villains, in a way—deserve credit. Still, I believe there should be an honest reckoning of what has happened. If for no other reason, it is a reminder of how far we have come.

6 Comments

What’s up, I read your blogs lіke every week. Your writing style is witty,

keep doіng what you’re doing!

Thank you very much for reading and for making a comment. As for the writing, I have been at this game a long, long time. What others have you read??

Very very interesting and detailed read. Learned a lot from this regarding college football and its integration. Thank you

So glad you enjoyed reading this piece about racial integration of college football. As you may notice, I have written many others to be found on this web site. Here is one: https://www.richardpennington.com/2018/05/celebrating-walk-ons-in-the-college-football-integration-story/

You really shorted the contributions of Wake Forest and its coach Bill Tate who along with the schools president, Harold Tribble, integrated Wake forest Football and schools made up of the old confederacy. Bob Grant and Butch Henry led the way and showed the ACC how good the black athlete could be. Grant would later be the `1st black player in the Old south to be drafted into the NFL as a second round choice of Baltimore. Later Wake would have the 1st black QB leading the Deacons in 1968.

Wake forest and its contributions are worth more then 2 lines in this article.

Oh, I suppose I “shorted” lots of people, but at least I mentioned these black guys. This was about the integration of college football from way back long, long ago. Should I write five paragraphs about Wake Forest? Sorry, no can do. And let’s give credit to their White coaches and White teammates who welcomed them to the team. And the White students at WFU, them too. Why don’t you write an article and I will review it? Abner Haynes was drafted by Pittsburgh in 1960, long before your Bob Grant.

Add Comment