Cheol-Woong Rim and I were a bit late in arriving at the National Palace Museum, adjacent to Gyeongbokgung—the biggest and most central of Seoul’s five royal palaces. The date was July 22, 2016, which meant that more than three years had passed since formation of the Committee to Bring Jikji Back to Korea. Twice before, we had met with representatives of the Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA), the government agency that protects and promotes the country’s vast treasures dating back 2,000 years and more.

They knew us, we knew them

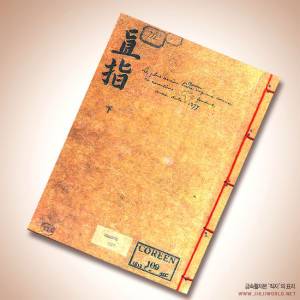

In 2014, some CHA people had visited us at LBC, the coffee shop/radio station run by Cheol-Woong. And the following year, we had been in this same room at the National Palace Museum. We were greeted by seven people, a couple of whom were actually with the Cheongju Early Printing Museum. For those who do not know, Jikji—the oldest extant document printed on movable metal type and thus tangible proof that the printing press derived from East Asia—was created in Cheongju in 1377.

This meeting came about only because I had written to President Park Geun-Hye, asking for 15 minutes to assert that the issue of Jikji should be near the top of the diplomatic agenda in bilateral Korea−France relations. Instead, one of her underlings directed the CHA to meet with this persistent NGO for a third time. Before we stepped inside the room, they knew our views and we knew theirs. I had considered declining this opportunity but thought it was best to meet with them since we were, in fact, talking with the Korean government.

To my left sat a relatively young woman, Hyun-Jung Seong. She did an excellent job of translating, both ways, during the 90-minute confab. After the preliminary niceties, I went ahead and stated our long-held and agreed-upon platform. Jikji, I said, had been in French hands long enough. It is a document of enormous cultural and historical significance, and its proper place is not the National Library of France. Since there is no proof that Victor Collin de Plancy bought Jikji in 1887, we assume he simply took it. I  gave some historical background, reminding them that the treaty signed by France and Korea in 1886 was of dubious value since one party (France) had power and the other (Korea) did not. The French essentially dictated the terms to the Koreans, and so de Plancy took Jikji in a neo-colonial context. Whether these Koreans enjoyed having a foreigner lecture them about their own history, I did not really care.

gave some historical background, reminding them that the treaty signed by France and Korea in 1886 was of dubious value since one party (France) had power and the other (Korea) did not. The French essentially dictated the terms to the Koreans, and so de Plancy took Jikji in a neo-colonial context. Whether these Koreans enjoyed having a foreigner lecture them about their own history, I did not really care.

I told them we now have more than 7,000 signatures on our petition and do not intend to stop until our goals are reached. That is not entirely true, as you will soon see.

Butting heads with Ms. Park

Directly across from me sat a lady whose name I did not catch, so I will call her Ms. Park. She would do most of the talking for the government people. She said in a rather long-winded way that there would be no change to the status quo unless we could offer some proof that Jikji had been looted, stolen or taken in some other nefarious way. On and on went Ms. Park. Cheol-Woong spoke now and then, rephrasing what I had said—Jikji should be returned to Korea as soon as possible and no strings attached. Back came Ms. Park with another long speech. Ms. Seong could not possibly have translated all that, as she must have known. Somewhat irritated, I interrupted in what I hoped was a not-too-rude way. I turned to Ms. Seong and said, “Please translate.”

One thing Ms. Park had been saying was that we should not seek “repatriation” of Jikji because that term has negative connotations. “I beg your pardon?” I retorted. “I am familiar with that word and can assure you it has no negative connotations whatsoever. In point of fact, that is exactly what we are calling for, the repatriation of Jikji. It cannot remain at the National Library of France in perpetuity.”

With Ms. Park yammering on, I had time to look around at the other five gentlemen. The one to her left I recognized from the first two meetings with the CHA. He seemed to have a bemused expression. I surmise he was thinking we were just clueless amateurs, and he had come all the way from Daejeon for a pointless meeting. Two others appeared to be fighting off sleep, while the last—a lawyer with whom I was also familiar—spoke up toward the end. A man (Kang Im-San) on our side of the table had been sneaking peeks at his smart phone during Ms. Park’s discourses. Mr. Kang informed us that he was with the Overseas Korean Cultural Heritage Foundation and that if we wanted to do work to publicize and venerate Jikji, he might be able to give us funding. I was noncommittal on that.

Rendez le Jikji a la Coree

I whispered to Cheol-Woong and urged him to say whatever he had to say, and he did. It was parallel with my earlier comments. The meeting, much of which took place when I needed to be in my office at the law firm, came to a graceful close. Cards were exchanged, and we went out into the hot summer sun. We posed in front of the entrance of Gyeongbokgung, holding a banner that said, “Rendez le Jikji a la Coree” (French for “Bring Jikji Back to Korea”).

That night, Cheol-Woong and I met again at LBC, but this time in company with his bilingual friend Ki-Eun Bae. With her help, I got a clearer picture of what had been said during the meeting. They had made reference to Voluntary Agency Network of Korea (VANK), an NGO which some people suspect is secretly financed by the government. If so, they are not really an NGO, are they? VANK’s position is exactly what Mr. Kang urged us to adopt—namely, concede that the French have Jikji and it will never return.

Our three-way discussion (regretfully, Yong Yoon, the other co-director of the Committee to Bring Jikji Back to Korea, was absent for both of these) lasted about an hour. I told Cheol-Woong and Ki-Eun that I have no desire to be a Jikji cheerleader if it must remain in Paris. From the start, back in June 2013, our cause has been singular: Jikji has to be brought home. Although we still hope to make some noise at the UNESCO / Jikji Memory of the World Prize ceremony in Cheongju on September 4 and in front of the French embassy in October, we are going to wind it down. Our campaign, which never had much chance of succeeding in the first place, will come to an end.

Add Comment