We have drought in much of the western United States, girls being subjected to genital mutilation in Africa, rampant corruption in Russia, a hopelessly failed state on the north end of the Korean peninsula, wars in Afghanistan, Syria and South Sudan, overpopulation, toxic waste, poverty, starvation, genocide, extinction of numerous species of animals and more. Maybe it’s not quite as serious an issue but I am puzzled that Abner Haynes still awaits induction to the College Football Hall of Fame and its professional counterpart. He should be in both, for reasons I will now state.

Haynes attended and played ball at Lincoln High School in Dallas, but segregation still held sway. Like every other black athlete at that time, he was ignored by the Southwest Conference schools and ended up walking on at North Texas State College (now the University of North Texas) in Denton. This was a guy whose skills were such that he should have been avidly sought by every football factory—I mean every institution of higher learning that fielded a football team. Even if the Texas schools were still intent on keeping their eyes shut, those out west, up north and to the east could have had Haynes by just asking. Instead, he had to walk on at rather obscure place like North Texas.

Let’s see what he did with the Eagles football team; he also ran track, by the way. He and Leon King were among the first batch of black undergraduates at NTSC. There were stormy moments when the freshman team went on the road as some fans seemed outraged by the idea of interracial athletic competition. Integration—or desegregation, if you prefer—was seldom an easy task. But the freshman Eagles did not crack. To the contrary, they bonded. Two black players and three dozen European-American ones looked out for each other on the field and off.

Haynes the pioneer

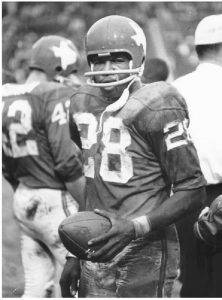

From 1957 to 1959, Haynes (6’ 0“ and 190 pounds) led the team in rushing, in scoring, in receiving, in kick and punt returns, and in interceptions. Yes, he was a fine defensive back! Twice all-Missouri Valley Conference, he even got some all-America votes in his senior year. The Eagles, coached by Odus Mitchell, went 9-1 and earned a spot in the 1959 Sun Bowl. Haynes was a superb player, a dynamic performer who helped his team in a variety of ways. During that time of waning segregation, people noticed. Haynes had played a major role in pushing the process of college sports integration forward. Soon, other schools like Angelo State, West Texas State, Texas Western and Texas A&I had brought in black players. Needless to say, they had an impact. Then came Warren McVea at the University of Houston and Jerry LeVias at SMU, by which time Jim Crow had been permanently and unceremoniously benched. Good riddance, too. In my view, the days before integration were like a fool’s paradise—something less than reality. That whole era merits an asterisk.

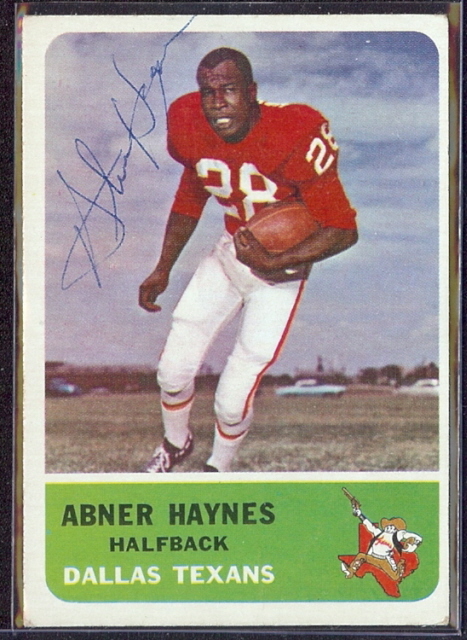

Once McVea and LeVias were starring with the Cougars and Ponies, respectively, Haynes was nearing the end of a very successful pro career that began in 1960. Rather than sign with the Pittsburgh Steelers of the NFL, he took a chance with a new team and new league. Hank Stram of the Dallas Texans thought Haynes had the talent and moxie to make his club one of the best in the American Football League, and was he ever right. Haynes did everything he had done at NTSC, other than playing defense. He was the 1960 AFL rookie of the year and MVP, and he led the Texans to the league championship in 1962 (notwithstanding his “we’ll kick to the clock” gaffe before overtime against the Houston Oilers). The Texans left Dallas and moved to Kansas City in 1963 where they became the Chiefs.

Don’t tread on him

Haynes was one of the leaders of a revolt before the 1965 AFL All-Star Game in New Orleans after it became clear that the city was unprepared to extend first-class treatment to black players. This action, a mere footnote in the Civil Rights movement, was still gutsy and significant; the game was hastily shifted to Houston. Two days later, Chiefs owner Lamar Hunt showed his gratitude and social awareness by trading Haynes to the Denver Broncos.

He also played with the Miami Dolphins and New York Jets before retiring. Haynes’ numbers are impressive: 12,065 combined yards (including 4,630 rushing for 4.5 yards per carry), and 68 touchdowns. He had scoring runs of 67, 59, 71, 46, 80, 47 and 65 yards, and caught TD passes that went for 69, 78, 73, 68, 71 and 52 yards. That’s what you call being a game-breaker. But he could also go up the middle for a much-needed first down. Whatever was necessary. Stram never lost sight of Haynes’ value: “He was a franchise player before they talked about franchise players. He did it all—rushing, receiving, kickoff returns, punt returns. He gave us the dimension we needed to be a good team in Dallas.”

BOTH Halls…

Admittedly, Haynes had a somewhat short career. And the last three seasons, he was not the dashing player he had been before. It should also be acknowledged that his peak was in the early AFL years, when the quality of competition did not equal that found in the rival NFL. But to me, that is all the more reason to see his luminous qualities as a runner, receiver and kick returner. Haynes did a lot to make the AFL a success in those crucial times. Gale Sayers of the Chicago Bears and Paul Hornung of the Green Bay Packers are somewhat comparable players—versatile guys whose careers overlapped with Haynes’. As much as I admire Sayers and Hornung, their talents and achievements were no greater than those of Haynes. Sayers was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1977 and Hornung in 1986; they got into the College Hall in 1997 and 1985, respectively. Abner Haynes is equally deserving. His contributions to college and pro football have not been sufficiently recognized, and so I hereby publicly nominate him for induction to both.

5 Comments

Amen. Don’t give up the Hall of Fame effort. Never give up!!

I appreciate that, Mr. Koontz. It seems that my devotion to Haynes just continues to deepen.

Please, tell me about yourself. How did you find my web site?

Sitting and talking right now with Abner right now . Great guy and a super football player. Needs to be elected to hall of fame

Both of them, Mike!

Wonderful article! He certainly merits this recognition.

Add Comment